The third and final day of the CILIP Rare Books and Special Collections group conference looked at Sale and Disposal: the unfortunate reality that libraries and collectors must sometimes part with their treasured collections, and how to make the best of an unpleasant situation.

Anastasia Tennant, a policy advisor for Collections and Cultural Property with Arts Council England, started the day with a presentation on Export controls on, and tax incentives available for the acquisition of, manuscripts, archives, and books. Since the 1910s, the United Kingdom has allowed the heirs of wealthy estates to offset a portion of their inheritance taxes by transferring cultural assets of significant value into public ownership. This tax exemption was originally intended for buildings and paintings, but from the 1950s onward, it could also be applied to literary archives, books, and manuscripts. In the 1960s, the regulations were revised to allow cultural assets to be allocated to regional museums, leading to a gradual increase in the proportion of archives that have been donated in recent years. More recently, the Cultural Gifts Scheme has allowed significant donations to offset other types of taxes as well. Because many libraries, archives, and museums rely heavily on donations to build their collections, tax incentives like these can encourage potential donors to give to local institutions instead of selling items of cultural value to raise capital to pay taxes.

By alleviating the financial burden of passing on valuable works of art, the exemption has prevented the loss of significant pieces of cultural heritage to overseas buyers. Since WWII, the United Kingdom has also had export controls designed to prevent capital from leaving the country. These procedures state that the directors of national institutions have the right to refuse an export license for works of art over a certain monetary value. In cases where an export license is refused, the owner must be presented with an offer to buy the item at a fair market price. If no institution is able to raise the funds to make an offer, it is possible that the item may still end up being sold overseas, but the hope is that a larger percentage of significant cultural artifacts will remain within the UK’s borders.

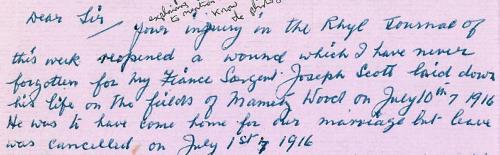

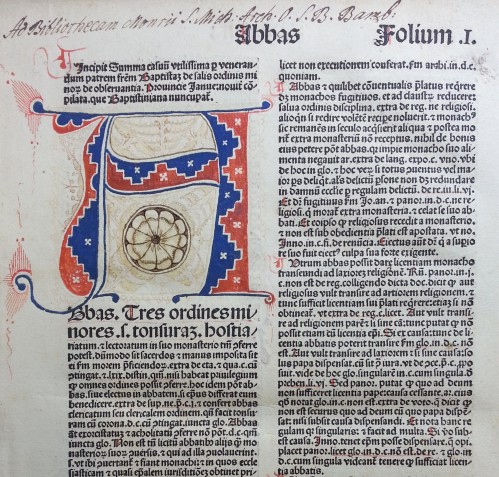

The second presentation by Alixe Bovey of the Courtauld Institute was a harrowing tale of the Law Society’s decision in 2012 to sell off the Mendham Collection. The Mendham Collection was formed in the early 19th century by Joseph Mendham, a clergyman who spent the later years of his life as a prolific controversialist and polemicist. In response to the Catholic Emancipation acts of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, he used his personal fortune to assemble a library (which he annotated heavily) of manuscripts, incunabula, and printed books in support of his anti-Catholic arguments. Ironically, in the process he built up a library that was particularly rich in both Protestant and Catholic history and theology.

In 1869, Sophia Mendham gave the bulk of her father-in-law’s collection to the Law Society, expressing a wish that the books be kept together as the “Mendham Collection”. A century later, the collection was placed on deposit with Canterbury Cathedral library where it was much used by students and faculty across two local universities. In the 1990s, the British Library awarded a grant to have the collection catalogued on the condition that no material would be dispersed at a later date. Although it was Canterbury Cathedral who assented to the terms of the grant, the Law Society seemed very proud of the achievement, and a print catalogue of the collection was published in 1994.

In April 2012, however, the library became aware that the Law Society planned to withdraw certain items with the longer-term goal of selling them. After unsuccessful attempts to communicate directly with the Law Society to prevent the sale, a campaign was launched and a task force assembled to preserve the collection. They gathered letters of support, set up an online petition, attracted media coverage, sought legal advice, and even offered to buy the collection from the Law Society, but in June 2013, the collection was split into 142 different lots and sold at auction by Sotheby’s. Another sale of 338 lots took place at Bloomsbury’s the following year.

Alixe Bovey points to a timeline of the Law Society’s decision to break up and sell the Mendham Collection.

Bovey speculated that the Law Society’s eagerness to sell may have been motivated by a significant downturn in the society’s finances in 2011. The society’s Annual Report for that year show a net deficit of £65.7m, compared with a £56.9m surplus the previous year. In the end, the actual revenue generated by the sale was approximately £1.6m.

Although still pained by the breaking up of the collection despite the best efforts of the library and its supporters, Bovey reflected on the bibliophile community’s willingness to come together in support of the collection, and the effectiveness of social media and other forms of publicity in preventing other bibliographic disasters like the proposed sale of Shakespeare folios from the Senate House Library in London. She also stressed the importance of cataloguing, noting that the 1994 print catalogue is now the sole surviving monument of the collection as a whole.

The final speaker of the conference was Margaret Lane Ford, speaking both as a representative of Christie’s auction house and as a member of the Bibliographical Society to offer a bookseller’s perspective on the dispersal of library collections. The Bibliographical Society recognises that weeding and disposal are necessary and appropriate parts of a responsible collection management policy, but that the decision to dispose of a collection should be made in an open and transparent manner, following careful thought and consultation.

To that end, the Bibliographical Society has a Libraries at Risk policy and subcommittee to help libraries who are faced with the prospect of selling a collection. The subcommittee can offer advice on whether it is possible or desirable to save the collection, raise the profile of the collection at risk, campaign to save the collection, or, failing that, help to find a new home for it.

Margaret Lane Ford presents some practical advice on dispersal from the book trade.

Collections may be sold in various ways, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. En bloc sales keep collections intact, but often make it difficult to find a buyer. Individual items may be offered for private sale, which can be discreet and move quickly, but can be perceived as secretive or underhanded, resulting in damage to the institution’s reputation. Collections may be sold at auction where there is the potential for items to sell above the estimated price, but also the risk that they will sell for less.

Booksellers can offer advice on how to achieve the best possible outcome from the sale and on handling publicity, an area in which few librarians have experience or expertise. Following the painful history of the Mendham Collection, Ford was eager to remind conference delegates that booksellers are the mechanism, not the catalyst for dispersal, and that they only become involved after the decision to sell has already been made. If a collection must be sold, library staff should not be afraid to make use of the knowledge and experience of members of the antiquarian book trade.

Following Ford’s presentation, there were a few announcements, a round of thanks to the speakers and the conference organisers, and then all that remained was to say goodbye to my colleagues and make the journey back home to Cardiff. Although this year’s conference presentations were filled with as many cautionary tales as success stories, I came away with lots of ideas for how to improve preservation and security for the collections in my care.