This guest post is from recent English Literature graduate Anna Sharrard. Anna took part in modules closely aligned with Special Collections throughout her final degree year, and is now volunteering with us over the summer, creating our first Edward Thomas online resource.

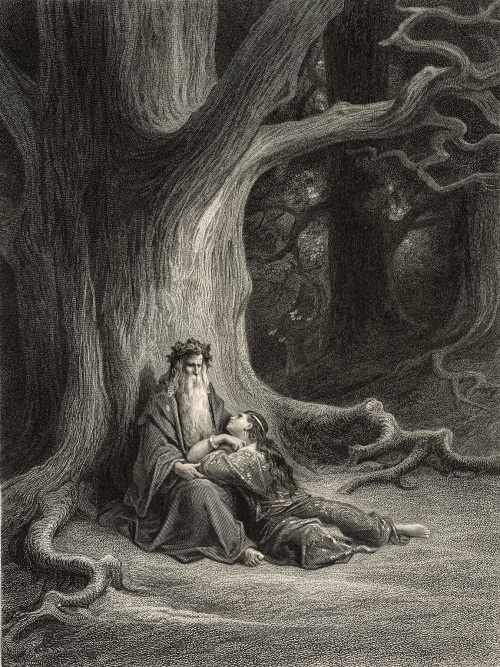

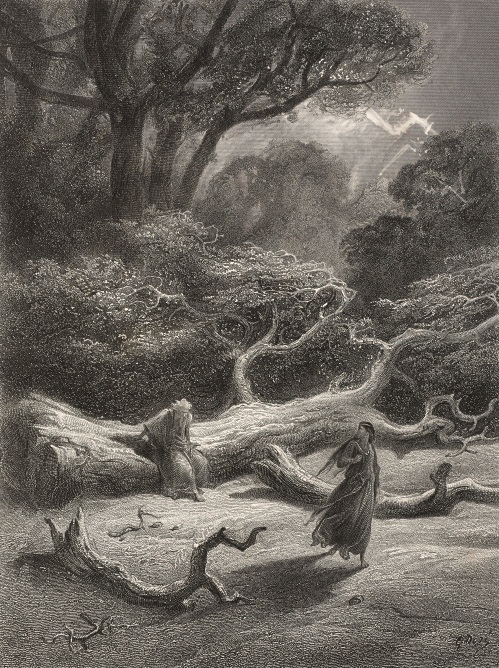

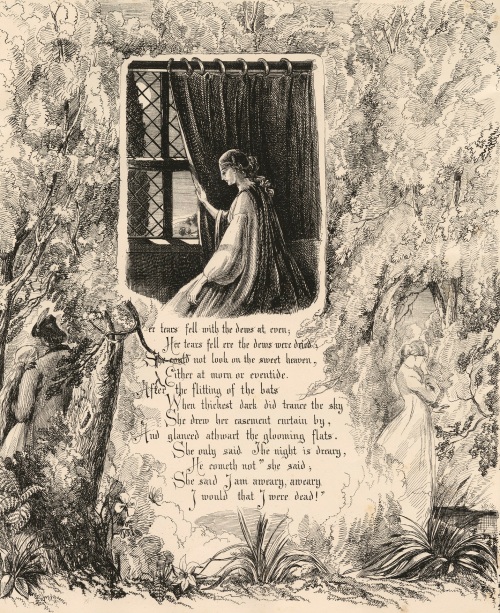

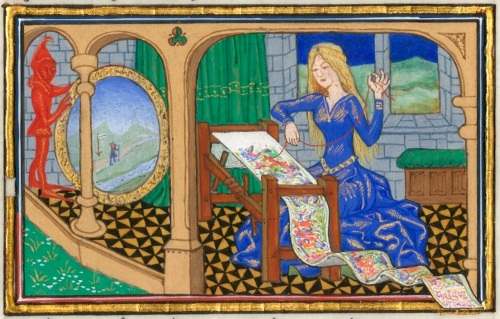

My first introduction to working in Cardiff University’s Special Collections and Archives was in the autumn term of my third year studying English Literature. I studied Dr Julia Thomas’s module, The Illustrated Book, which hosted all of its seminars in Special Collections. Over the course of the module, we were given access to numerous examples of illustrated novels, journals, and newspapers from the archive’s extensive collection, aiding our understanding of the history of the illustrated book from the late eighteenth century to the present. My personal highlights included studying Special Collections’ copy of the Moxon Tennyson (surely every Pre-Raphaelite lover’s dream), handling the unconventional and intriguing artist’s books, and carving our own designs into lino blocks to attempt relief printing for ourselves! (Safe to say, I don’t think we would have made the cut to be professional engravers any time soon…)

I was excited by the prospect of returning to the archive in the spring term while studying Dr Carrie Smith’s module, Poetry in the Making: Modern Literary Manuscripts. In order to give us practical experience of working with literary manuscripts, several weeks of the module were conducted in Special Collections, engaging with the material held in the Edward Thomas (1878-1917) archive. Part of the assessment required us to create a group video presentation exploring an item of interest from the archive. Here’s a clip from one of the student films:

Despite the words ‘group presentation’ usually striking fear into the hearts of most students, the filmed assessment was what had initially attracted me to the module. To have a practical element to an undergraduate English Literature module is unusual, and it stood out as a unique opportunity, allowing students to develop and showcase a different set of skills to future employers.

Special Collections’ Edward Thomas archive is expansive, holding the world’s largest collection of his letters, diaries, notebooks, poems, photographs, and personal belongings. Alison Harvey, archivist at Special Collections, selected a wide array of material from the archive for us to explore, and in our groups we assessed which items would form the focal point of our presentations. Being tasked with working with archival material was certainly a new experience, and it proved very interesting but also challenging. Almost all the texts I had encountered during my three years studying English Literature had been published documents, written in standardised print with titles, page numbers, and footnotes. It was therefore challenging studying the manuscript form of Edward Thomas’ poems, diary entries, and correspondence, because the layout of the text on the page did not always follow a chronological pattern. Amendments and notes could have been added at different stages of the document’s history, and we felt like detectives trying to figure out the chronology of the documents. At the beginning we also struggled with some of the seemingly indecipherable handwriting, but both Carrie and Alison were extremely patient with us, and with practice, it became easier to interpret the handwriting and read the material.

I think the rest of the group would agree how surprisingly evocative they found the experience, especially handling the telegram sent to Helen Thomas relating the news of her husband’s death, and reading the condolence letters sent to her by Edward’s comrades and friends. I think these documents produced a strong emotional reaction among the group, because holding correspondence of such a personal nature felt intrusive to some extent. It was possible to imagine the moment Helen received the telegram, and the devastation this would have caused her and their three children.

The practical experience of working hands-on with the archive material and filming for the presentation made an invigorating change from the usual essay assessments, and the module was an excellent introduction to working in an archive. It also sparked a personal interest in Edward Thomas, drawing in all the elements of his life as a literary critic, a novelist, a poet, a soldier, and also as a husband and a father. I was able to delve further into his life and works by attending the Edward Thomas Centenary Conference that was held at Cardiff University in April 2017, hearing leading researchers of Edward Thomas speak, and meeting fellow fans of his work. On one of the days of the conference, I participated in a student panel hosted by Dr Carrie Smith, answering questions from the attendees about our experience of using the archive, handling the material, and producing a video presentation as an assessment, which was understandably identified as an unusual feature of an undergraduate module.

Special Collections also launched its Edward Thomas 100 exhibition to coincide with the Centenary Conference, and it was fantastic to see the collection showcased to the public in such a visually appealing and accessible way. Much respect to Alison for engineering such a wonderful display whilst also fending off frequent queries about the Edward Thomas archive from our course group as deadlines loomed! The exhibition is on display in Special Collections until October, for any of those who are inspired to come and have a gander.

After being involved in the conference, I approached Alison to see if I could be of any assistance in volunteering my time to Special Collections over the summer. She proposed a project to digitise sections of the Edward Thomas archive. The plan was to focus on the photographs, poems, and letters held in the collection, which were used so heavily as an educational resource every Spring by Dr Carrie Smith’s Poetry in the Making group. Since July, I have been tasked with digitising, editing, uploading and organising images on a freely available online resource (Flickr), where they can be viewed and navigated through easily. The resource allows images to be downloaded for re-use at a variety of resolutions.

Once uploaded to Flickr, I attach the full metadata to each image to assist with citations, add tags (so that images can be found by users searching keywords) and a location pin (if applicable). Finally, I group related images into albums for ease of navigation.

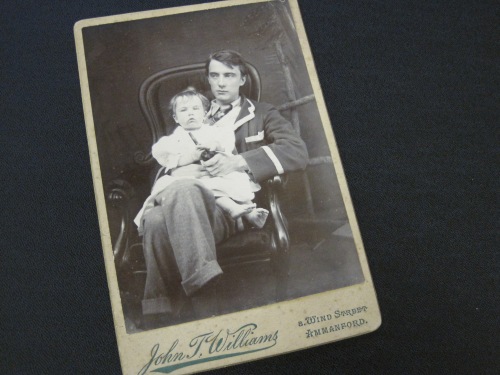

I began by tackling the extensive collection of photographs, beginning with those solely of Edward Thomas, and then moving onto the wider family, including ones taken years after Edward’s death. It was necessary for me wear gloves to handle the photographs, (completing the stereotypical image of an archivist in style I might add), as the oils from the skin can easily damage the surface of the prints.

It has been pleasing to see the Flickr account fill up with photographs of Edward, his wife Helen, and children Merfyn, Bronwen, and Myfanwy. The images really help to flesh out their lives outside of Edward’s publications and literary career. You get a sense of character through photographs that it can be difficult to find from a sheet of paper, no matter how personal someone’s handwriting can feel. It was also enjoyable to see the progression of Edward and Helen’s three children growing up as the number of photos on the resource accumulated.

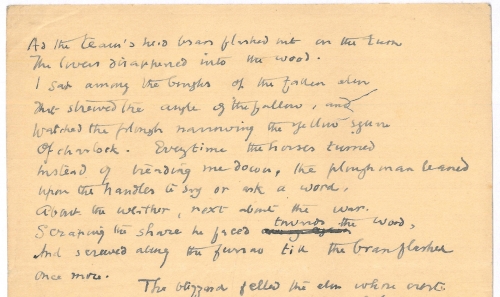

I encountered one of the more challenging aspects of working with archival material when I moved onto digitising Edward’s poems. The manuscript poems held at Special Collections date between 1914-1917, and the pages are noticeably thinner and more delicate than other material in the archive. This is because paper quality severely declined during wartime, and its high acid content makes surviving material extremely friable. The availability of digital surrogates will help conserve these vulnerable originals.

To get a representative sample of the hundreds of letters stored in the archive, I focused my attention next on Edward’s letters from poet Robert Frost and those sent to writer Gordon Bottomley. The letters which I chose to upload from Gordon Bottomley date from 1902-1905, and reveal evidence of Edward’s continuing struggle with depression. Though mostly containing discussion of literature and Edward’s review-writing, there is often a pervasive tone of despair to Edward’s letters. The letters sent to Edward written by Robert Frost date from 1915-16, and are saturated with the outbreak of the war, revealing insecurities arising from the pressure of enlisting and needing to prove one’s worth. On pages 3-4 of a letter from 6 Nov 1916, Frost writes:

“You rather shut me up by enlisting. Talk is almost too cheap when all your friends are facing bullets. I don’t believe I ought to enlist (since I am American) […] When all the world is facing danger, it’s a shame not to be facing danger for any reason, old age, sickness, or any other. Words won’t make the shame less. There’s no use trying to make out that the shame we suffer makes up for the more heroic things we don’t suffer.”

Edward’s own desire to prove his worth is evident in a letter he wrote to his daughter Myfanwy. Dated 29 Dec 1916, whilst Edward was situated in Lydd, Kent, he confesses:

“I should not be surprised if we were in France at the end of this month. I do hope peace won’t come just yet. I should not know what to do, especially if it came before I had fully been a soldier. I wonder if you want peace, and if you can remember when there was no war.”

Another extensive sequence of Edward Thomas’s correspondences held in Special Collections is between Edward and Helen Thomas (nee Noble). These letters run from 1897 (before their marriage), until Edward’s death in 1917. Of the hundreds of letters, I selected the last letters Edward wrote to Helen, and worked my way backwards. I thought this would provide a useful contrast to the early Bottomley letters, also identifying that the descriptions of Edward’s experiences in the army, and his subsequent posting to France, would be of great interest to researchers of Edward’s life.

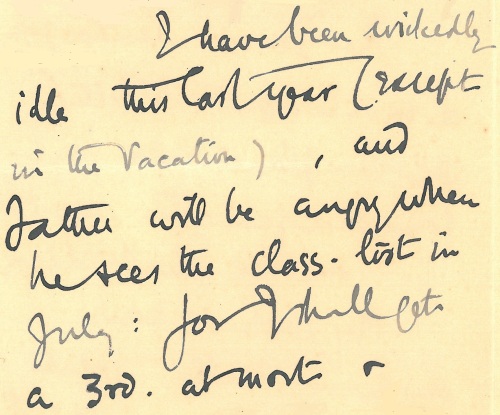

The letters Edward writes to Helen during the years he is studying at Lincoln College, Oxford (1898-1900), whilst Helen is at their family home in Kent, are interesting because they disclose the domestic side to Edward’s life. These letters may consist of comparatively mundane subject matter to researchers, as they consist of everyday conversations, mainly including practical matters and financial arrangements between the couple. However, much of the early correspondence resonated with me. One particular letter (25 May 1900, pp. 5-7) contains Edward’s dejection over getting a bad mark in a university module and worrying about disappointing his parents.

“I have been wickedly idle this last year (except in the vacation), and father will be angry when he sees the class list in July: for I shall get a 3rd at most.”

Every student at some point has gone through the angst of being convinced they were going to fail a module. It’s reassuring that this was also the case for the last century’s students too.

Another letter from a month later, (8 Jun 1900), consists of Edward expressing his misery at being apart from Helen, but her not being able to visit him because of financial constraints and having nowhere for her to stay. Despite these letters being over 100 years old, it is remarkable just how relevant they still are to students, and to my own experience of being in a long-distance relationship. In our age of instant communication, we can forget how much further distances just within the UK would have felt when you had to wait on a letter to bring news of your loved ones: “I have no time for a letter but I can’t help expecting to hear good news from you. The absence of it is distracting. My health is getting bad and my eyes almost // failed me today. I don’t see how you can come down. You can’t afford it and I don’t know where you could stay.”

In creating this resource, I have become privy to so many more aspects of Edward Thomas’s life that I didn’t have time to appreciate during the seminar hours of Poetry in the Making. My hope is that this resource will allow future students on the module to spend time going through the collection at their own leisure, unrestrained by the archive’s opening hours or the limited number of seminars held in the archive. Having the images freely available to use on Flickr will reduce the number of times the documents will be handled each time a group needs to take a photograph, helping to conserve the originals. This will free up time during the seminars for the groups to discuss the content and argument of their presentations, and also guarantee high quality photographs for every group. For those rushing things last-minute, (as there inevitably will be), they will be able to check a reference number or a date quickly online, rather than having to pull out and go through all the boxes of material in search of one photograph or a letter they forgot to write down the catalogue number for!

Beyond the University, now that a large chunk of the Edward Thomas archive has been digitised, researchers all over the world are able see images of the documents described by the archive catalogue, and can easily browse through the majority of the collection held here in Cardiff. This will be a major help to many, I hope, and aid them in their research.

I’ve enjoyed my time in Special Collections very much over the final year of my degree here at Cardiff University, and I want to say a big thank you to the entire team at Special Collections for making me feel so welcome during this project. It’s been a pleasure to aid future users of the archive, and if you’re unfamiliar with Special Collections, I hope you will go for a visit after reading this!

![Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson's Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes?].](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/elaine_mss.jpg?w=500&h=600)

![Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson's Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes?]](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/vivian_mss.jpg?w=500&h=686)