This guest post comes from Natalie Saturnia and Molly Patrick, undergraduates in English Literature, who took part in a research placement this summer as part of the Cardiff Undergraduate Research Opportunities Programme (CUROP). Natalie and Molly worked as research assistants on Dr Melanie Bigold’s project, ‘Her books: Women’s Libraries and Book Ownership, 1660-1820’. Dr Bigold’s project aims to create the first comprehensive database collection of women’s libraries in the long eighteenth century.

Travel and the Eighteenth-Century Woman

Natalie Saturnia

My post, funded by the Cardiff Undergraduate Research Opportunities Programme (CUROP), was focused on finding and organising the preliminary research databases. My daily work included transcribing and cataloguing the booklists identified by Dr Bigold, and trying to identify specific editions of texts using databases such as the English Short Title Catalogue.

Frontispiece of Thomas Maurice, The History of Hindostan (1795)

While spending time with booklists of influential eighteenth-century women such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Elizabeth Vesey, and Elizabeth Greenly, I noticed a prominent lack of fiction texts across their catalogues. Before embarking on my research placement, I had assumed that most of the texts literary women owned would include fiction and the classics. While their lists still included a number of novels, particularly in Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s collection, their catalogues also contained a considerable quantity of travel texts. Because this was a surprise to me, it piqued my interest and I chose to do further independent research to figure out the reasoning for their travel collections.

Detail from Thomas Maurice, The History of Hindostan (1795).

My initial reaction when I saw the quantity of travel books was that it showed a desire in these women for knowledge beyond their own domestic borders. Alison Blunt writes that,

work on British women travellers has focused on their ability to transgress the confines of “home” in social as well as spatial terms. The travels and writings of individual women suggest that they were empowered to travel and transgress in the context of imperialism while away from the feminized domesticity of living at home.[1]

While this specific quote only refers to female travellers who documented their own journeys, perhaps the same can be assumed for women who read and owned travel writing. In the case of Lady Mary Montagu, she did travel, yet she also collected travel books. This, along with her own documentation of travel in her Turkish Embassy Letters, proves that she valued the experience and knowledge gained while traveling and felt she was enriched because of it. One of her travel books Le Gentil Nouveaux Voyage au Tour du Monde (1731) translates to the ‘the nice new trip around the world’. This text possibly reflects a desire in Montagu to learn and study parts of the world she had not travelled to, which again demonstrates the value she placed on travel.

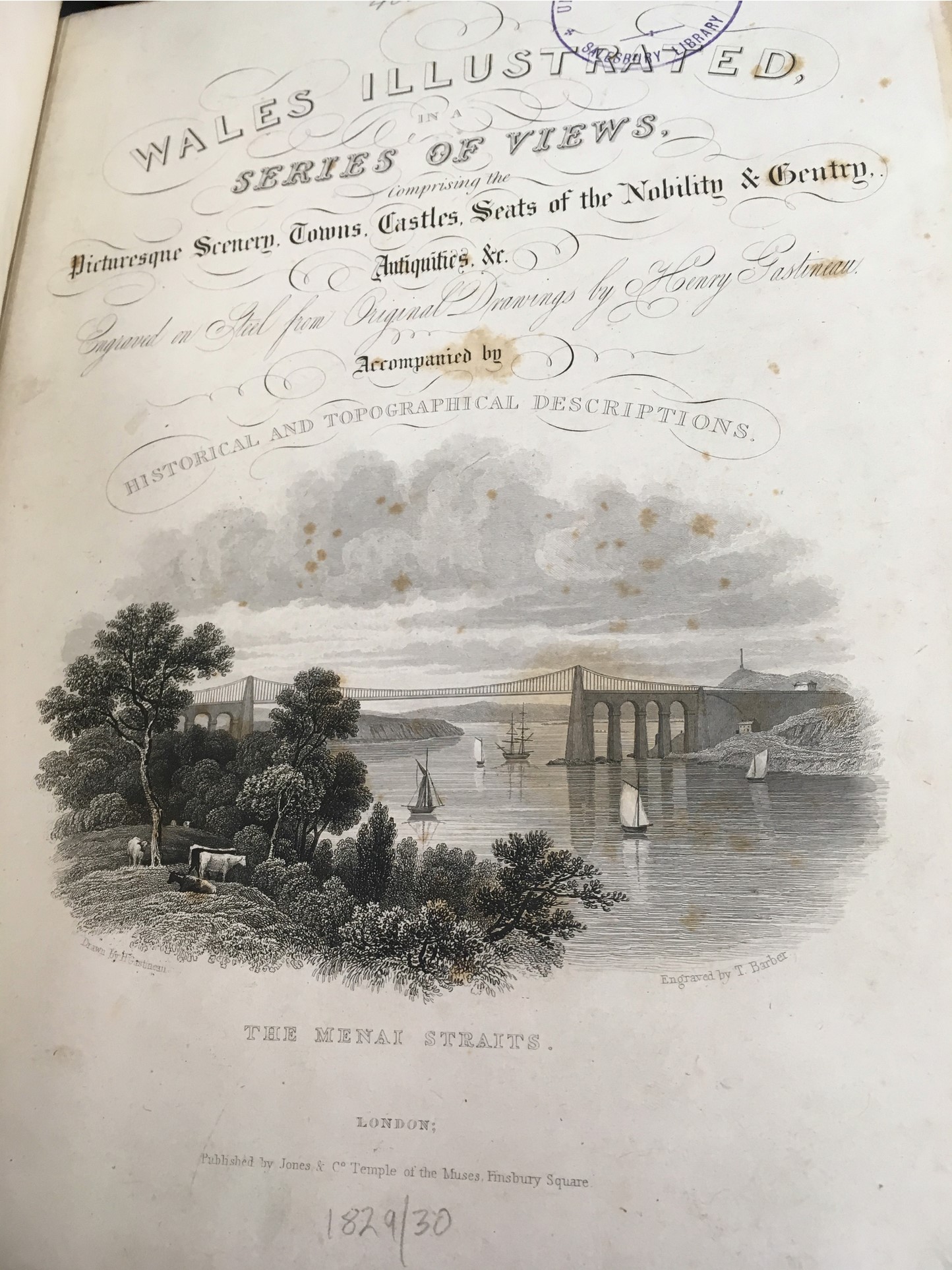

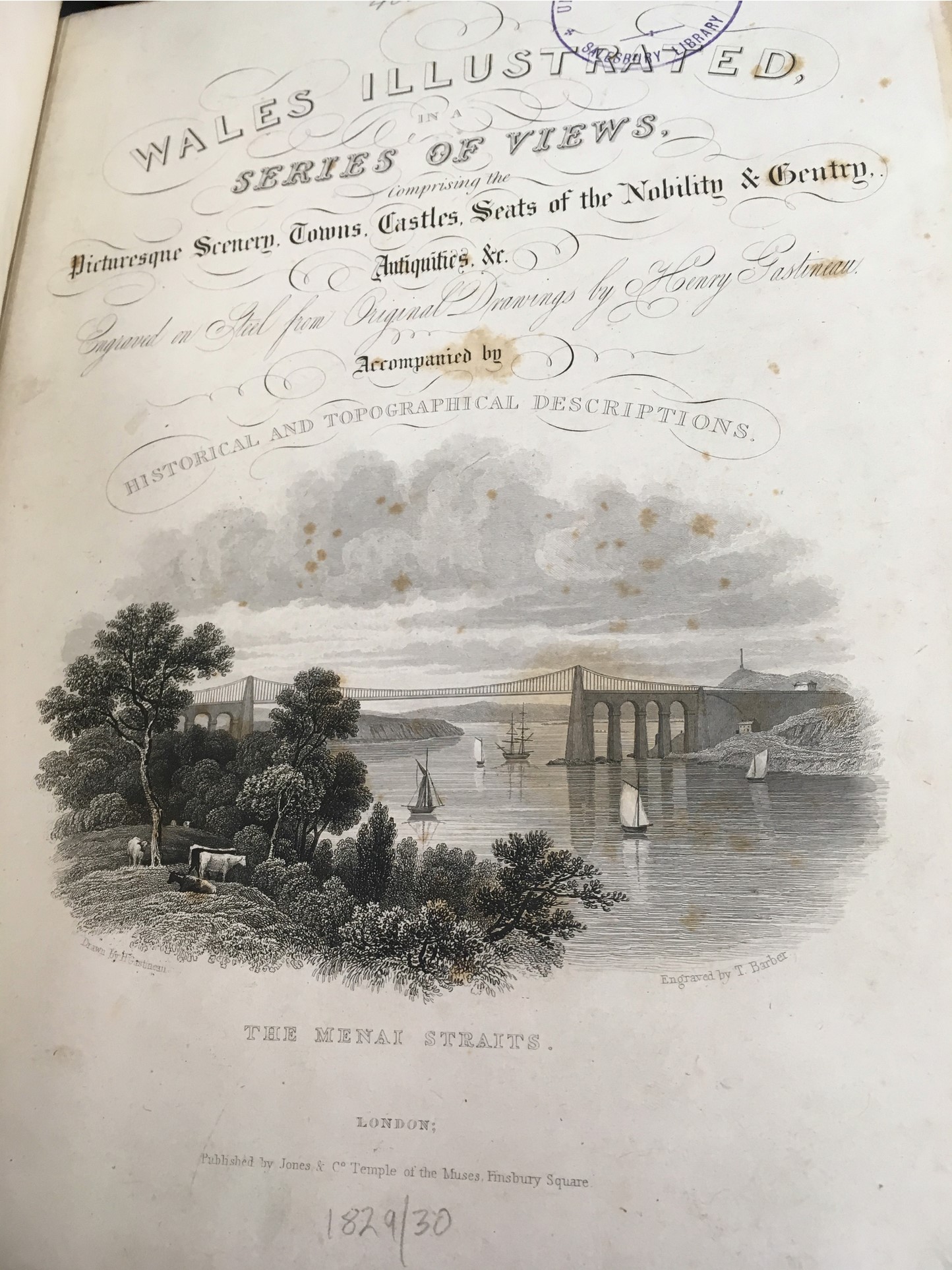

In contrast to the other women I researched, Elizabeth Greenly’s book list contained a large collection of Welsh travel books, such as Wales illustrated: in a series of views by Henry Gastineau and Wanderings and excursions in North Wales by Thomas Roscoe.[2] Born in Herefordshire, Greenly later lived in Wales and maintained a lifelong interest in all things Welsh. Before she became less active later in life due to a stroke and rheumatoid arthritis, she used to ride her horse between Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Glamorganshire, and Breconshire. Her collection of Welsh travel books exemplifies an early sense of Celtic pride which is further evidenced by her ‘ardent support of Welsh causes of the day, including Iolo Morganwg (Edward Williams 1747-1826).’[3] Greenly’s detailed knowledge of the Welsh border counties clearly enhanced her desire for literature on the surrounding area. It may also have been the case that, as a local gentlewoman, she was actively supporting Wales-related books through her purchases.

Henry G. Gastineau, Wales illustrated, in a series of views (1829?-1830)

Ultimately, I believe that these women, whether or not they were privileged enough to travel themselves, valued the insight that travel books provided. Travel books about places foreign to them allowed them a glimpse into parts of the world they were unable to experience first-hand. As for travel books of familiar places, it often represented and reinforced a sense of identity. Indeed, as an expat myself, I am acutely aware of how integral geographical location is in relation to identity. More importantly, I think travel, whether across short or long distances, instilled in these women as sense of pride in their own intrepid spirit. Their library collections speak to that spirit of travel, adventure, and self-creation.

While ‘Her books: Women’s Libraries and Book Ownership, 1660-1820’ is still a work in progress, the new perspectives I gained and conversations I started during my month of research on these women’s catalogues has ignited my own research ambitions. Most importantly, though, the process has highlighted the many new insights that a comprehensive catalogue of female book owners during the long eighteenth century will provide.

[1] Alison Blunt, ‘The Flight from Lucknow: British women travelling and writing home, 1857-8’, Writes of Passage ed. James Duncan and Derek Gregory (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 94.

[2] Henry G. Gastineau, Wales illustrated: in a series of views, comprising the picturesque scenery, towns, castles, seats of the nobility & gentry, antiquities, &c (1829?-1830) and Thomas Roscoe, Wanderings and Excursions in North Wales (1836).

[3] Dominic Winter, Printed Books & Maps (2016), p. 83.

Divinity Books in Women’s Libraries: Teaching Femininity

Molly Patrick

![Sarah Jones' inscription in The Christian Life [1695], by John Scott.](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/sarah-jones_-inscription-in-the-christian-life-1695-by-john-scott.jpg)

Sarah Jones’ inscription in The Christian Life [1695], by John Scott.

The eighteenth century was an important period in the history of women’s literary participation. The growth of personal libraries coincided with this increased engagement and book collections reflect, as Mark Towsey argues, the intellectual and cultural aspirations and values of their owners.

[4] Elizabeth (Smithson) Seymour Percy, the first duchess of Northumberland, Mrs. Katherine Bridgeman and

Elizabeth Vesey all had extensive personal libraries which featured many advice-giving divinity books. By examining what these texts teach women, it is possible to see how femininity in the eighteenth century was constructed and justified using the authority of God.

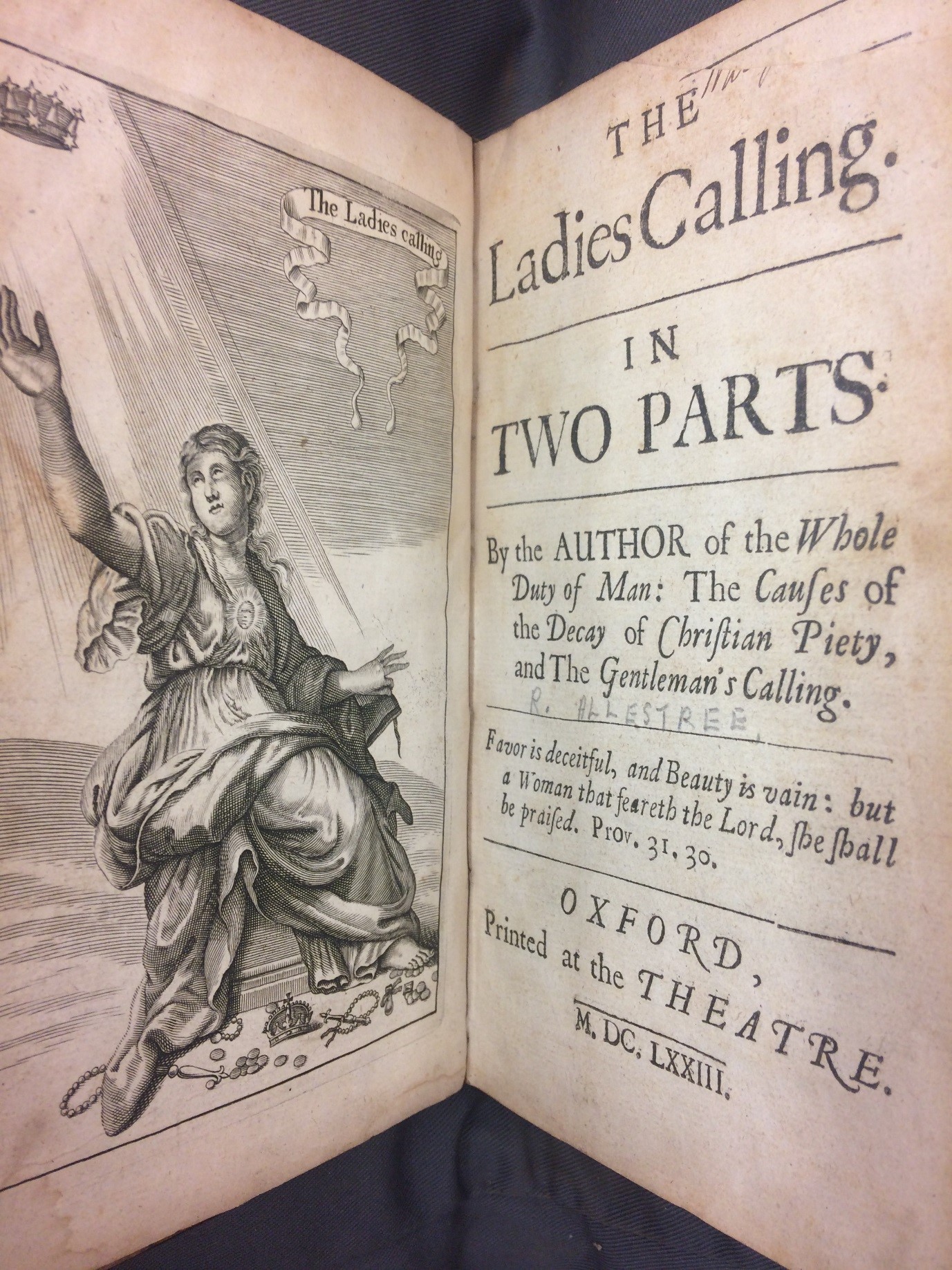

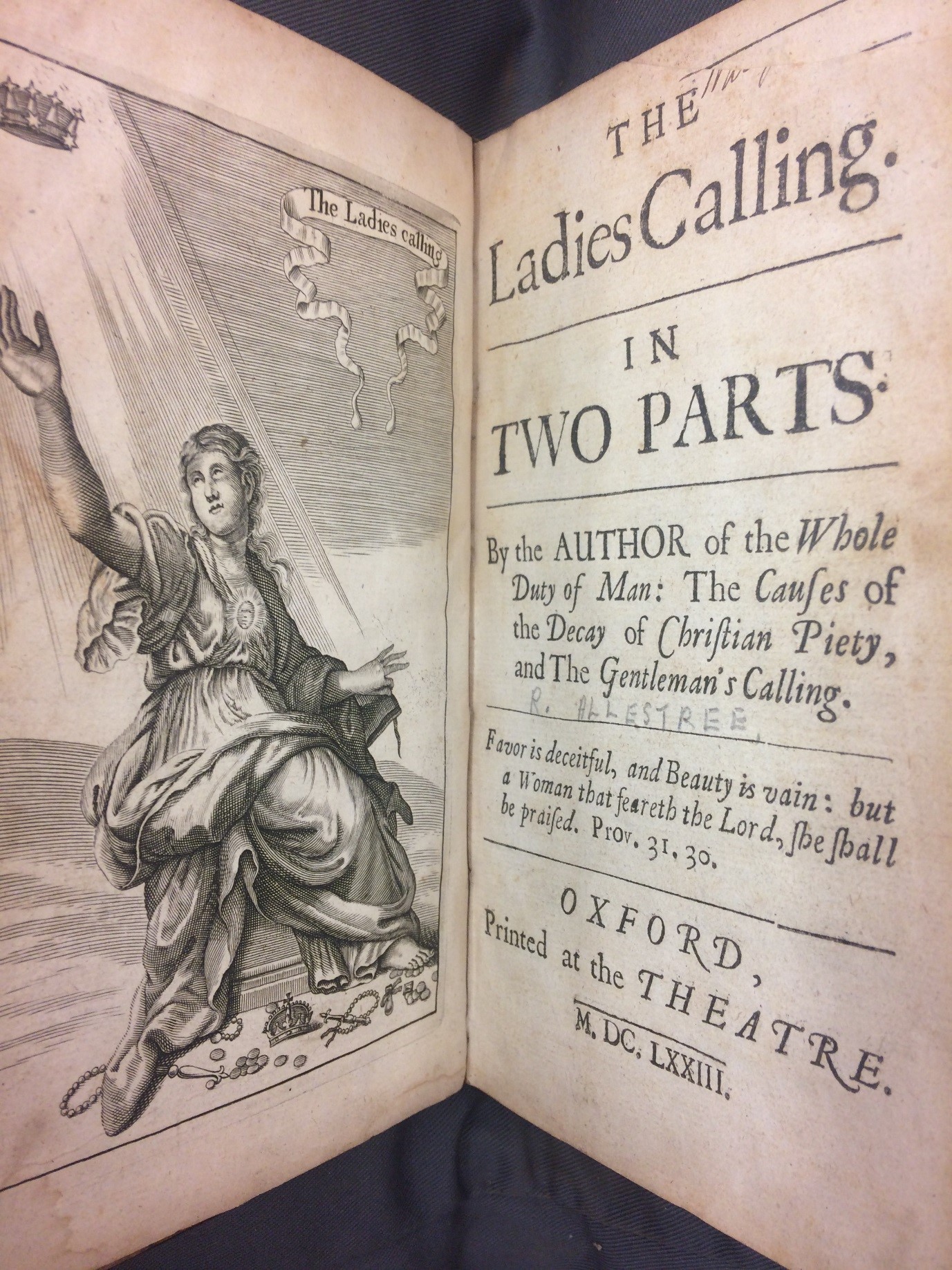

Elizabeth Seymour’s library catalogue includes a sub-section dedicated to Divinity texts, many of which function as pedagogy. Featured in Seymour’s collection is The Whole Duty of Man by Richard Allestree (first published in 1658). In the chapter entitled ‘Wives Duty’, women are given advice on how to conduct themselves in marriage. They are told that God will ‘condemn the peevish stubbornness of many Wives who resist the lawful commands of their Husbands, only because they are impatient of this duty of subjection, which God himself requires of them.’ This shows that religious, devotional works were often used to establish women’s subordinate position, using God as an authority to these teachings. The book also gives specific instructions regarding how the wife should act if asked to do something ‘very inconvenient and imprudent’ by her husband: she should ‘mildly […] persuade him to retract that command’, not using ‘sharp language’ and she should never steadfastly ‘refuse to obey’. Clearly restricting the wife to a passive, subordinate role, this passage confirms the unequal power dynamics of seventeenth-century marriage. In addition, The Whole Duty of Man blames women for men’s sinful behaviour: ‘how many men are there,’ Allestree asks, ‘that to avoid the noise of a forward wife, have fallen to company-keeping, and by that to drunkenness, poverty and a multitude of mischiefs’. Here, a stereotype about the nagging wife are held against women in general.

Richard Allestree’s The Ladies Calling (1673). The copy in Special Collections belonged to an seventeenth-century woman, Elizabeth Scudamore.

Richard Allestree’s sequel, The Ladies Calling (1673) and The Causes and Decay of Christian Piety (1667) also appear in the divinity section of Seymour’s personal library collection. The Ladies Calling questions the origin of gender inequality, but nonetheless reproduces a similar message advocating a subordinated, passive femininity. Allestree avers that ‘in respects of their intellects [women] are below men’; however, ‘Divinity owns no distinction of genders’ as ‘in the sublimist part of humanity, they are their equals.’ The Causes and Decay of Christian Piety, on the other hand, inscribes the argument that religiously devoted women pose a threat to established gendered roles. Allestree contends that ‘when women neglect that which St. Paul assigns them as their proper business, the guiding of the house, their Zeal is at once the product and excuse of their idleness’. Indeed, Allestree implies that women only seek religious vocations in order to avoid their natural place in the domestic sphere. In this sense, divinity texts from the eighteenth century not only advise women to be passive and subordinate, but also caution them against turning to a religious life.

Katherine Bridgeman’s collection evidences a similar interest in divinity texts. In her edition of The Rules and Exercises of Holy Living (1651), Jeremy Taylor advises that women should ‘adorn themselves in modest apparel with Shamefacedness and Sobriety, not with broidered hair, or gold, or pearl, or costly array’. This narrative of passive femininity permeates a multitude of divinity texts in Bridgeman’s collection, such as in Robert Nelson’s The practice of True Devotion (1721). Nelson defines women’s ideal religious expression as ‘their chastity’ and ‘modesty’, which are both passive acts signifying a withholding as opposed to active expression. Both Bridgeman and Seymour’s collections feature divinity books which promote a repressed, subordinate version of femininity and it could be argued that their libraries reflect a wider view of women and their place in eighteenth-century contemporary society.

The content of the books featured in Elizabeth Vesey’s library, however, offer an alternative view of women, femininity and their place within religion. One such work that exemplifies this difference is Robert Barclay’s Apology for the True Christian Divinity: being a Vindication of the people called Quakers (first published in 1678). The text openly disputes women’s subjugation within religion and the established church. Barclay contests the idea, apparently deriving from ‘the church’, that ‘women ought to learn […] and live in silence, not usurping authority over man’. Barclay notes that, in St. Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians, the apostle writes rules concerning ‘how Women should behave themselves in their publick preaching and praying’. This, he argues, is evidence that early religious figures did not refute women’s right to actively express their religion. Deborah Heller points out that Elizabeth Vesey was accumulating her library at the same time as significant changes were happening in literary, social and cultural environments. Around the mid seventeenth-century, ‘owing to the proliferation of novels and conduct literature, there was a rapid transformation, and a powerful new identification of women with subjectivity’.[5] The presence of Robert Barclay’s book in Vesey’s library seems to confirm women’s alignment with greater religious subjectivity.

In conclusion, the personal library collections of Elizabeth Seymour and Katherine Bridgeman include a multitude of pedagogical divinity books. These texts encourage women to be passive, subordinate to men and to avoid public religious activity. Elizabeth Vesey’s book collection, however, seems to inject a different narrative. Taking Robert Barclay’s Apology for the True Christian Divinity as an example, it is possible to see how Vesey’s collection, unlike the books found in Seymour’s and Bridgeman’s libraries, focus on women’s religious and personal empowerment. Vesey’s collection demonstrates a possibility of different cultural and social aspirations, an alternative way of thinking about women’s role in contemporary society.

[4] Deborah Heller, ‘Subjectivity Unbound: Elizabeth Vesey as the Sylph in Bluestocking Correspondence’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 65.1 (2002) pp. 215-234. P. 218.

[5] Mark Towsey, ‘‘I can’t resist sending you the book’: Private Libraries, Elite Women, and Shared Reading Practices in Georgian Britain’, Library and Information History, 29.3 (2013), 210-222 (p. 210).

![Sarah Jones' inscription in The Christian Life [1695], by John Scott.](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/sarah-jones_-inscription-in-the-christian-life-1695-by-john-scott.jpg)