This guest post comes from Lauren O’Hagan, PhD candidate in the School of English, Communication and Philosophy, who is researching early 20th century book inscriptions and reading practices in Great Britain.

The World’s Your Oyster… Unless You’re a Girl:

Exploring Historical Gender Inequality in Prize and Gift Books

From the #metoo campaign to the gender pay gap, in recent months, the topic of gender inequality has seldom been out of the headlines. Since the early twentieth century, bolstered by the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union, women in Britain have been fighting for equal rights and opportunities. While images of imprisoned suffragettes on hunger strike or members of the Women’s Liberation Movement burning bras are ingrained in our minds as early examples of the struggle against gender inequality, there is one form of historical discrimination that remains largely forgotten, despite the fact that it is still prevalent in our society today: the giving of books as gifts and prizes. The full extent of this highly gendered practice only became apparent to me through a delve into the Janet Powney Collection at Special Collections and Archives.

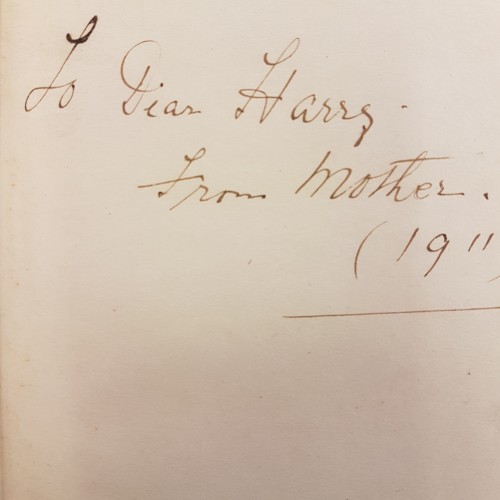

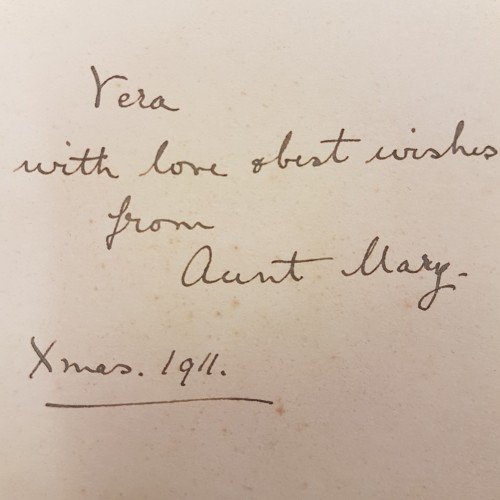

The Janet Powney Collection is made up of some eight-hundred children’s books, largely dating from the late-Victorian and Edwardian era. These books were predominantly given as gifts or awarded as prizes to children and, as such, most bear an inscription on their front endpaper.

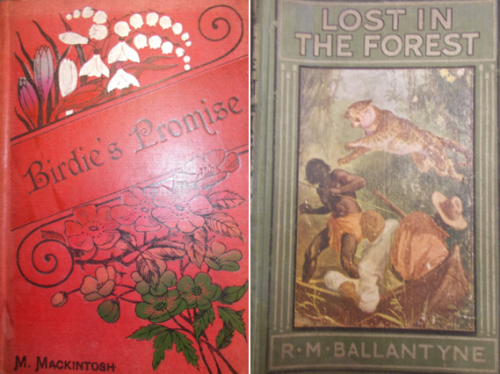

The years 1880 to 1915 are generally considered to mark a key period in the development of a distinctive girls’ and boys’ culture in Britain. Nothing illustrated this distinction more obviously than books. As book production grew and new designs and modes of distribution developed, publishers began to recognise the commercial potential of identifying specialist readerships, particularly girls and boys. Taking advantage of the emerging ‘vanity trade’ in which buyers were strongly influenced by a book’s outer appearance over its internal content, publishers produced books whose images, typography and colours were heavily influenced by gender.

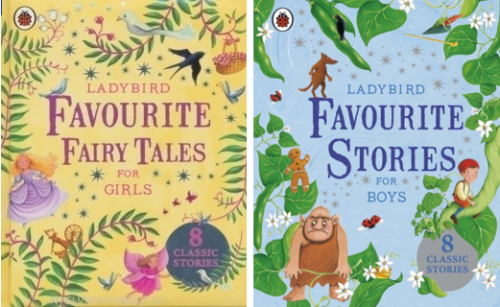

More than one hundred years later, these same marketing strategies can be observed in children’s books today, as seen in the photo below from Waterstones taken by the #LetToysBeToys campaign group.

Books are, of course, not the only objects to have become genderised. From a young age, advertisements (and indeed many parents) are still largely responsible for teaching children that dolls are for girls and cars are for boys. The breadth of this issue and the various debates it provokes have most recently been demonstrated by John Lewis’s decision to introduce gender neutral clothing lines for children. While many people praised the progressive move of John Lewis, arguing that “you don’t look at food and say it’s going to be eaten by a man or a woman, so why should it be any different for clothes?” others criticised the retailer for “bowing down to political correctness.” The mixed responses that this topic has generated indicates that, now more than ever, it is necessary to return to the past in a bid to improve the future.

Books as Gifts

What it meant to be a girl and a boy in Victorian and Edwardian Britain can be clearly seen through the inscriptions made in gift books within the Janet Powney Collection.

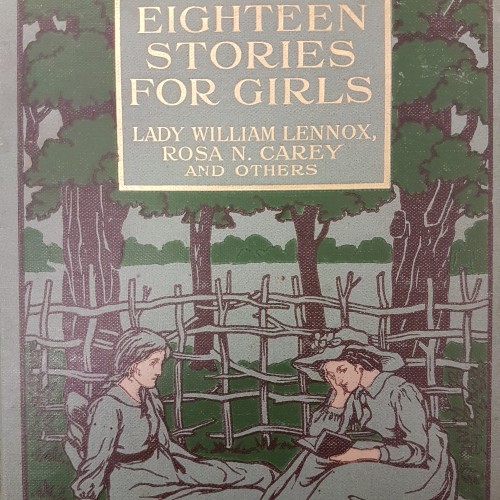

For girls, religious fiction was most frequently gifted, primarily by their mothers, grandparents and friends. Religious fiction emphasised traditional female qualities of sacrifice and obedience and encouraged girls to uphold the conventional role that had been pre-established for them in society: that of being a wife and a mother. In contrast, boys were chiefly given adventure fiction by their mothers, grandparents and friends. Adventure fiction promoted cultural expectations of masculinity, and focused heavily on the notions of imperialism, heroism and comradeship. For both boys and girls, it was the mother who inscribed the book; the father’s name was conspicuously absent. The Victorian scholar, Kate Flint, claims that the mother was generally considered the most appropriate person to choose a book for her children – a belief that still prevails today (please click through to request access to the article from the author).

The fact that the same split into religious fiction for girls and adventure fiction for boys can also be observed when friends gave each other books as presents indicates that the purchaser of the gift was typically an adult, i.e. the child’s parent, and so, it was their views on gender appropriacy that were given overriding priority. The book historian, Jonathan Rose, claims that girls’ books only sold well because they were chosen as presents by adults, and, in fact, many Victorian and Edwardian girls preferred adventure fiction and often read their brothers’ copies surreptitiously. Adventure fiction was discouraged for girls, as it was deemed harmful to their ‘fragile’ minds and risked diminishing their value as females.

Despite these gender stereotypes that were largely influenced by the giver’s concept of what was suitable for the receiver, the collection has one notable exception: in all examples of Aunts giving books to Nieces, the books belong to the adventure fiction genre. While this suggests that the modern-day concept of the ‘cool aunt’, in fact, has its origins in the late-nineteenth century, this theory falls apart slightly when noting that nephews continued to receive adventure fiction, with no examples of religious fiction given. This gives weight to the widely asserted claim by the scholar, Barry Thorne, that it is more acceptable for girls to associate with masculinity than boys with the lesser valued and ‘contaminating’ femininity.

Many of the above points are still relevant in today’s society. While religious fiction has largely disappeared from bookshops with the increase in secularisation, it has come to be replaced by the romance genre – perhaps a reflection of the growing acceptance of girls’ sexuality, yet still stereotypical in its own way. Boys’ fiction, on the other hand, continues to be dominated by adventure and fantasy novels. Despite the fact that a recent survey demonstrates that comedy is now the favourite genre of most boys and girls in the UK, with David Walliams and Jeff Kinney being cited as the favourite authors of both genders, when it comes to gift-giving, many family members and friends still resort to stereotypical genres and authors. Equally, while it is now widely acceptable for girls to receive Harry Potter or Hunger Games books as gifts, for example, very few boys are the recipients of books by Jacqueline Wilson or Jill Murphy. Although the Representation Project is attempting to challenge and overcome gender stereotypes by encouraging parents to buy books for children based on their individual personalities and interests instead of defaulting to gender-specific gift options, these findings show that there is still clearly a long way to go.

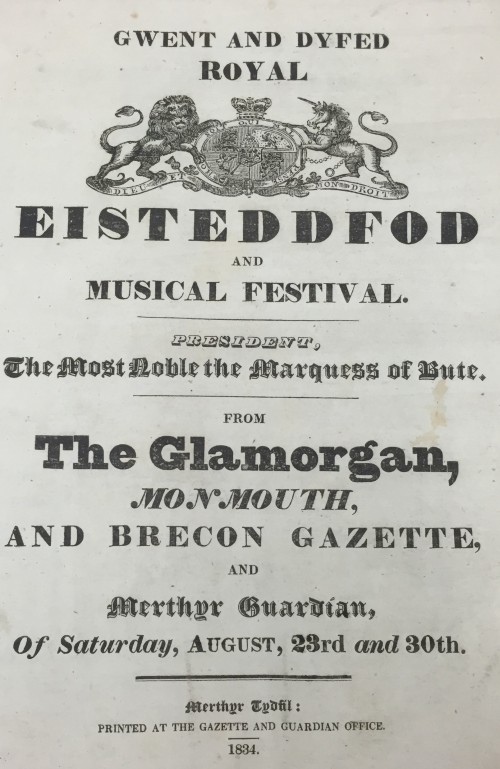

Books as Prizes

Throughout the Victorian and Edwardian era, awarding books as prizes was standard practice for most schools, Sunday schools and other institutions across Britain and its Empire. While these books were typically awarded in recognition of an outstanding achievement or contribution, they also served a secondary function of moral education and they were often used by educational and religious institutions as tools to disseminate approved fiction. Writing in 1888 in favour of prize books, the literary critic, Edward Salmon, argued:

“The young mind is a virgin soil, and whether weeds or rare flowers and beautiful trees are to spring up in it will, of course, depend upon the character of the seeds sown. You cannot scatter literary tares and reap mental corn. A good book is the consecrated essence of a holy genius, bringing new light to the brain and cultivating the heart for the inception of noble motives.”

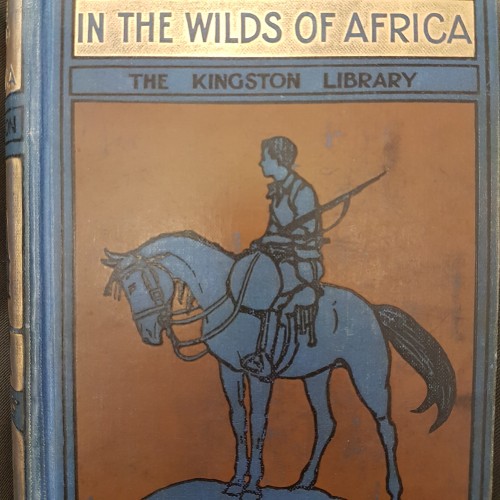

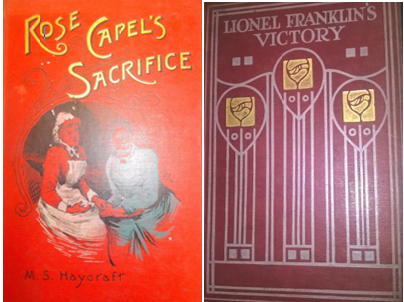

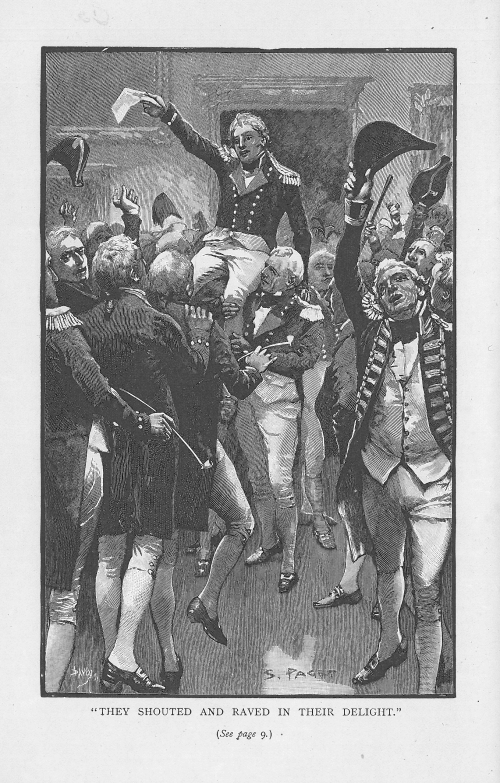

The prize books in the Janet Powney collection generally reflect similar trends to the gift books, although there is some variation according to awarding institution. For example, within Sunday schools and faith schools, both boys and girls were most likely to receive religious fiction. As the prize book movement was largely aimed at bringing respectability to working-class children, religious fiction was considered the most suitable type of book to provide appropriate models of behaviour to boys and girls. More importantly, however, educators saw religious fiction as a ‘safe’ and ‘reliable’ book genre that advocated conventional masculine and feminine roles. These gender differences are explicitly reflected in the titles of prize books: ‘sacrifice’, ‘obedience’ and ‘barriers’ most frequently occur in girls’ titles, while ‘winning’, ‘voyage’ and ‘victory’ feature most regularly in boys’ titles. These words demonstrate that girls were expected to live a contained life with limited opportunities and within local boundaries, but boys had the freedom to explore the global picture and the choice to do as they wish.

Despite supposedly having no religious affiliation, board schools also favoured religious fiction as prizes for girls; in contrast, boys were awarded adventure fiction. In some cases, boys were also given history and biography books, which tended to emphasise the view that to be British was to be a conqueror, an imperialist and a civilising force. This fits with the argument of historian, Stephen Heathorn, that the Victorian and Edwardian elementary classroom served as a workshop of reformulated English nationalism.

Although most prize books awarded by clubs were directly liked to their ethos (i.e. Bible classes distributed Bibles, Choirs presented music books etc.), many clubs still showed gender bias in their choices. For example, both religious and secular clubs awarded books to boys that focused on temperance and the criticism of other vices, such smoking, gambling and pleasure-seeking. These books also placed great attention on the importance of chastity and the concept of chivalry as a means of self-control. These issues were highlighted, as educators feared a supposedly causal link between boys’ crimes and reading matter that influenced them. Boys’ books also focused on the importance of saving money and owning a house, which fit with the traditional view of ‘man as economic provider’.

The girls’ book given by both religious and secular clubs, on the other hand, focused heavily on the notion that moving out of one’s social station was against God’s will and often warned girls of the dangers of switching religious allegiances. As the ‘weaker’ sex, girls were considered more likely to become ‘corrupted’, particularly by Catholicism, which was believed to be strongly linked to the forces of social and political reaction, moral decadence and foreign treachery at this time.

While such stark gender inequalities may not be as apparent today in prize-giving practices, they still prevail in some institutions, albeit covertly. Sunday schools throughout Britain still promote the awarding of ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ books. Seemingly innocent titles, such as ’10 Boys Who Changed the World’ or ’10 Girls Who Changed the World’, in fact, reveal that the boys are all involved in dynamic actions as sailors, smugglers or gangsters, while the girls are confined to lowly positions as slumdogs and orphans, or have physical and mental impairments.

Even within non-religious institutions, such as state schools, prize books remain gendered with neutral stories, such as ‘Cinderella’ and ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’, creeping into volumes labelled as Favourite Fairy Tales for Girls and Favourite Stories for Boys respectively. Although book titles no longer appear to use stereotypical adjectives to define boys and girls, just like in Victorian and Edwardian Britain, they remain ladened with gendered words: witches, fairies and unicorns dominate girls’ books, while dinosaurs, castles and football are exclusive to boys’ books. Recently, the National Union of Teachers carried out a Breaking the Mould Project to encourage nursery and primary classrooms to challenge traditional gender stereotypes through books. They recommended awarding books, such as Anne Fine’s Bill’s New Frock or Robert Munsch’s Paper Bag Princess to engage with the range of ways in which children can be stereotyped. Given the complexity of this topic, it is unsurprising that many schools have now opted to award book tokens instead of books to avoid the difficult act of choosing.

A child’s home and educative experience has a direct effect on his or her short-term and long-term achievements and is responsible for shaping his or her pathway in life. For this reason, it is important to engage with historical artefacts, such as the books in the Janet Powney collection, to learn from negative representations of gender. By using the gift and prize books to map particular attitudes to and constructions of gender, we can correct any potentially harmful behaviours that still remain in our society and strive towards living in a country with gender equality for all.