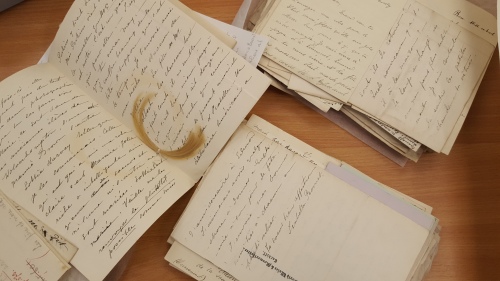

After completing her work on the Barbier archive, our CUROP intern Katy Stone shares her final, fascinating discoveries about life in the French army at the end of the nineteenth and turn of the twentieth century.

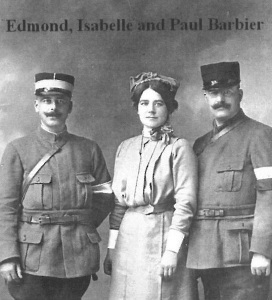

For my final blog about the Barbiers I’d like to share some contrasting discoveries about Cardiff-born Georges and Jules Barbier’s experiences of military service with the French Army, revealed through their heartfelt letters written from 1898 to 1904. As shown in a blog by last year’s CUROP student Pip Bartlett, all of the Barbier brothers – due to their dual nationality – completed mandatory national military service with the French Army well before the First World War, with both Georges and Jules subsequently remaining ‘poilus’, or ordinary field soldiers.

Georges Barbier and the comfort of letters in Le Mans

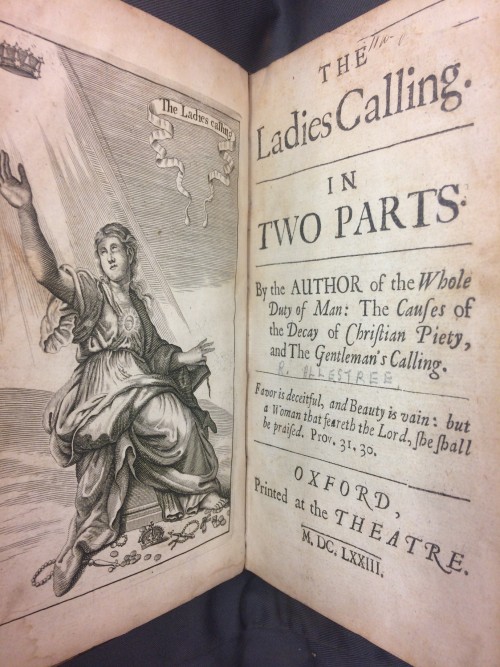

In 1899 Georges Barbier was deployed to the 26th Artillery in Le Mans and many of his letters support Pip’s previous insight that, out of all the family members who went to war, he undoubtedly suffered the loneliest military experience. In one letter dated 3 February 1899, he paints a dark picture of the stark living conditions within his regiment, describing his barracks as a “dirty shack” and expressing gratitude to his brother, Paul Barbier fils, for writing to him – “it is such a blessing to receive letters in this hole”. Georges was clearly unhappy in his regiment and their frequent exchange of letters was not only a source of comfort, but also a channel for escapism. To make things worse, he appears to have found it difficult to fit in with his peers – “all those who sleep in the same room as me are vagabonds, so I have no luck at all”. Hard work was, surprisingly, a blessing in disguise for Georges and I was struck to find him striving for more – “The work is very hard, but that I don’t mind in the least for when I have plenty of work I have not time to worry, which is a very good thing for me”. This eagerness throws light on the mental challenges faced by many soldiers on a daily basis – he was “completely disgusted with life” and would “rather do hard labour than be controlled by a lot of morons who can’t read”.

Barrack detail from a letter dated 20 Februray 1899

Other letters give an insight into his basic military diet – “I live on bread and cheese and once a week I eat meat, on Sundays”. It was also surprising to learn that Georges had to pay for his military meals out of his own pocket, and that his limited financial means meant there was no spare money for any luxuries – “I find that I eat very little here. I have no appetite, and not only that but I have to pay for everything I eat”. A letter to his mother, Euphémie, dated 31 January 1899 reinforces the daily struggle faced by the majority of his peers – “I was so ashamed to buy for so little that I nearly broke down, when there was a lot that could not do as much”. Life was tough in the French Army and although stress and anxiety may have been accountable for his poor appetite, the demands of the physical work also contributed to his struggles with mental and physical health. In his letters he complains of toothaches, headaches and sore feet, yet despite “suffering a great deal”, he avoids going to see the doctor because he “would have to stop work, not only that but I would be unable to go out in the evening”. Another letter sheds light on his perception of being treated differently to his French peers due to his British identity – “You know I have been very sick and had to get treatment in town because the major refused to recognise me … I believe it’s because I’m English”.

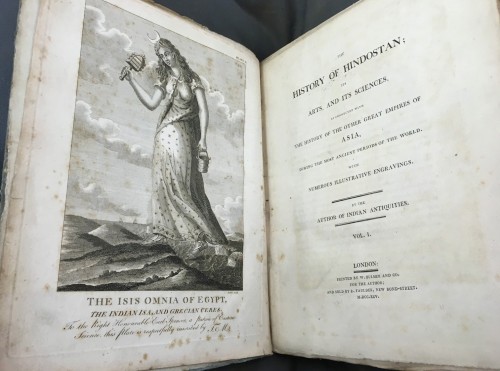

Insignia of the Soissons Regiment, 1899

Jules Barbier “far from being miserable” at Soissons

Jules Barbier seems to have experienced a far less despondent national service with an infantry in Soissons. He recalls being “received very kindly” at the barracks, and remarks that “there are some nice boys” and “all the officers have been very kind”. In contrast to the discrimination faced by Georges at Le Mans, Jules mentions that his captain remarked “it was very nice of me to come and do my service from England”. This would have no doubt boosted his enthusiasm and spirits, enhancing his military experience and possibly reinforcing his bond with his French heritage. The Barbier Archive gave me the impression that Jules, to some extent at least, enjoyed his work in the French infantry, often describing his activities in a buoyant tone – “Yesterday I was taught to salute and about different ranks of officers. I was given my rifle, and tomorrow we will exercise”. This is in stark contrast to the more physically demanding and draining responsibilities encountered by Georges.

Self-portrait of Jules E. Barbier in a letter to his mother, 5 August, 1899

Like Georges, however, Jules often reported that money and food were particularly scant, referring to himself as being “as poor as a church mouse”. In one letter dated 11 February 1899, he feels ashamed for having to borrow 15 francs from a friend, alluding that money was a lingering concern. All his money was solely spent on necessities – “I’m just eating, I’m always hungry”, suggesting that there was no such thing as disposable income in the French Army. Despite having a more positive experience than his brother, Jules’s time in the military was also hampered by illness; “I am in the infirmary. Last bed. I was taken ill with a fever and also with my throat in fact. I have got an abscess there and it is very painful”. But the fact that he was admitted to the infirmary, and a promise that his captain “would come to see me in the hospital”, suggests that the quality of pastoral care was far superior to that experienced by Georges. In one letter Jules announces “I am far from being miserable” and is eager to return to his duties – “Time passes very slowly here in the hospital. I would be pretty eager to go back to the barracks”.

Early colour printing of a barracks scene, 1899

When I embarked on my summer placement with the Barbier Archive at Special Collections and Archives, I did not expect to discover such contrasting personal accounts of life in the French Army through the eyes of the sons of Cardiff. Sometimes harrowing, often spirited, but always heartfelt, this fascinating archive paints a vivid picture of everyday life at a time when the world was on the cusp of one of its most turbulent periods. It has been an absolute indulgence to be able to tease out yet another remarkable story in Cardiff’s history.

![Sarah Jones' inscription in The Christian Life [1695], by John Scott.](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/sarah-jones_-inscription-in-the-christian-life-1695-by-john-scott.jpg?w=500&h=667)