This guest post comes from Dr Lauren O’Hagan, sociolinguistic researcher of Edwardian material culture and class conflict.

“He is not quite a cow, but a little green bull

He lives in a large field where there is no up and no down

He always wears beautiful trousers

You may like him at first, but you will soon get tired of him

He is very pretty, but oh, so good!

He collects nothing”

Read the above lines and you’d be forgiven for thinking that they came from one of Quentin Blake’s nonsense verses or a lost Dr Seuss book (minus the rhymes!). In fact, they are taken from Behind the Night-light, a 1912 book that captures the poetic musings of a three-year-old girl, Joan Maude. Back in December of last year, I shone a spotlight on another Edwardian child star: Daisy Ashford and her successful novel The Young Visiters. Like The Young Visiters, Behind the Night-light was also a bestseller in its day, only to have faded into obscurity over time. I’d like take the blog space this week to acquaint unfamiliar readers with this delightful and forgotten book.

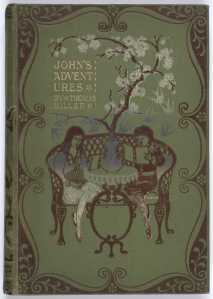

Behind the Night-light was published by John Murray in June 1912 and went through four reprints in its first six months. It is its fourth reprint from January 1913 that graces the shelves of the Janet Powney Collection in Special Collections. Considering the way that most children’s books of the period were decorated, the book has decidedly bland black cloth covers. However, tucked within, page after page is filled with intriguing and humorous tales about an original world that little Joan Maude created from the comfort of her childhood playroom.

According to the title page, every story and poem in the book has been “described by Joan Maude and faithfully recorded by Nancy Price” (her mother). As Price explains in the preface:

“These quaint beasts who roam that delightful country ‘behind the night-light’ are the exclusive discovery of a child of three. Their names, their habits, etc., are entirely hers. My task has merely been to record them in language as near the original as possible.”

And this originality is certainly apparent in the contents page alone as we are introduced to such unique characters as the Kiddikee, Boo-Choo and Fat-Tack to the Mossip, Hitchy-Penny and Jonket. Through Joan Maude’s imagination, we learn about Bomblemass, an animal who “grows no teeth, carries a stick, wears a green plush coat and ties on his legs with black silk ribbon” or the Gott family “who all lost their ears because they wouldn’t listen.” We meet the Stickle-Jag “who has a coat made of hundreds and thousands, so that he can eat bits off of it when he can’t find the sugar basin” and the Lowdge who “collects dust and lives in the middle of it.” And so on and so forth across its fifty pages of creativity.

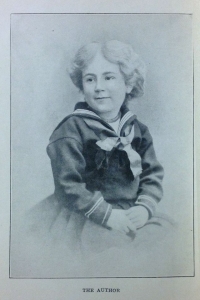

A key factor that influenced book sales was the fact that Joan Maude wasn’t just any little girl; she was the daughter of Nancy Price (1880-1970), a huge star of the Edwardian stage. Price had been part of F.R. Benson’s theatre company for many years, touring extensively in the provinces performing Shakespeare plays. In 1902, she caught the attention of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree who cast her as Calypso in Stephen Phillips’ production Ulysses at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London. She later went on to play Hilda Gunning in Letty (1904), Mrs D’Aquila in The Whip (1909), one of the Pioneer Players in The First Actress (1911) and India in The Crown of India (1912). This meant that at the time of the book’s publication, she was perhaps as famous and recognisable as any of the big Hollywood stars today. Price would go on to establish the People’s National Theatre in 1930, as well as the English School Theatre Movement, which toured productions of Shakespeare plays to working-class children. She was awarded a CBE for services to the stage in 1950.

Upon release, Behind the Night-light was met with tremendous praise by the newspapers. The Era (8 March 1913) described it as “a collection of quaint and original animal fancies” and the Norwood News (12 December 1913) called it “a revelation of wonderful things, while The Pall Mall Gazette (8 June 1912) claimed that the monsters would have found a friend in Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky.

One year after the book’s publication, Nancy Price enlisted the services of Joan Maude’s godmother, Liza Lehmann, also an English operatic soprano and composer, to turn the book into a stage show. By summer 1913, Behind the Night-light was playing all across England from the Manchester Theatre Royal and Bedford Town Hall to Torquay Pavilion and Ilkley King’s Hall. Reciting the rhymes were such big stage names as Jeannette Sherwin and Guide M. Chambers, and even Nancy Price herself at one special performance in London.

Up until the late 1920s, Behind the Night-light was also a favourite musical for schools to perform. Local newspapers raved about how pupils in Sevenoaks performed the songs at the Royal Crown Hotel (Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser, 30 November 1917), as well as how children at Steyne School in Worthing put on a show for an enthusiastic audience at Connaught Hall (Worthing Gazette, 7 November 1923). It is also claimed by Nancy Price that many of the expressions from the book went into common use and could be heard amongst such varied people as a professor of history and a pavement artist. “Don’t be a gott” was used to describe someone with a bad temper who wouldn’t listen and “a lowdge” became a term for somebody who ran very quickly.

Being the daughter of a famous actress and finding fame herself at such an early age meant that Joan Maude was always destined for stardom. In 1921, at the age of 13, she made her stage debut in Cairo at His Majesty’s Theatre in London. By the time she hit adulthood, Joan Maude had already starred in more than twenty stage productions all across the West End. As the ‘talkies’ became popular in the 1930s and 1940s, Joan Maude made her move from the stage to the screen, starring in a wide range of comedies, dramas and romances. Perhaps her most famous role was in Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946).

After some fifteen years of popularity, Behind the Night-light stopped touring, schools ended their performances of the musical and sales of the book decreased. Whether the novelty of the book had simply wore off now that Joan Maude was all grown up or whether she herself wanted to distance herself from the book that had first made her famous remains unclear. Nowadays, Behind the Night-light is practically unknown; a cursory Google search brings up just 33 results.

Looking at Behind the Night-light today, perhaps the most surprising observation is the book’s complete absence of images. With such rich descriptions of a world conjured up by Joan Maude, it is a real oversight not to have accompanied the text with vivid illustrations. This may have also secured the book’s longevity as children grew attached to such characters, remembered them more distinctly and then passed them onto their own children. 2020 will mark fifty years since the death of Nancy Price. To me, this seems like a glaring opportunity for a publisher to pick this book back up, update it, populate it with colourful imagery and introduce these charming characters to the children of today.