I know what you’re thinking – only my third post and I’m talking book crazy! Well, working in Special Collections it was bound to happen sooner or later, though I’d be lying if I blamed my current state of mind on the awesome collections here; I’ve always been mad about books.

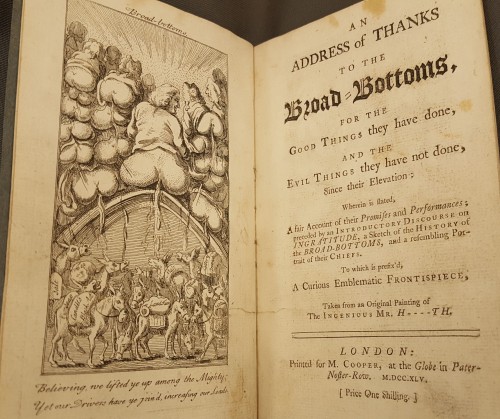

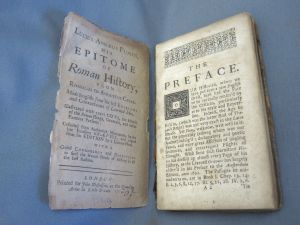

So enthused in fact, that not even the huge spider in our Research Reserve could deter me from one of my rummaging sessions (he was scrunched up dead, but I was still petrified!) which, incidentally, led to another where the following titles also jumped out at me:

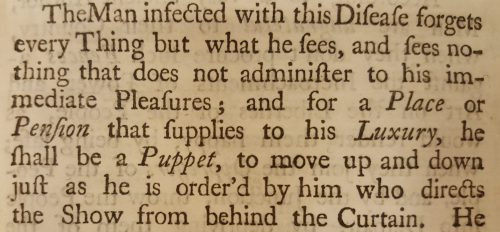

Bibliomania describes the ‘passionate enthusiasm for collecting and possessing books’, and was first coined by the physician John Ferriar in 1809. In a poem he dedicated to his friend, The Bibliomania: An Epistle to Richard Heber Esq’, Ferriar describes Heber as ‘the hapless man, who feels the book disease’, whose ‘anxious’ eyes scans the catalogues of book auctions to ‘snatch obscurest names from endless night’. Heber was an English book collector and one of the founding members of the Roxburghe Club, an exclusive bibliophilic and publishing society for like-minded book lovers and collectors. (Note: do not confuse bibliomania with bibliophilia which is not as bad as it sounds, merely the great love of books!). Incidentally, another founding member, Thomas Frognall Dibdin, published Bibliomania: or Book Madness in 1809, a sumptuously illustrated work set as a series of dialogues on the history of book collecting. It’s interesting that the notion of Bibliomania is seen as some kind of folly or affliction. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the budding culture of reading brought about by the growth of print and literacy was often described as some sort of endemic. Reading-fever, or even reading-lust was one aspect of this, characterised by the compulsive reading of one book after another.

This brings to mind the famous Welsh linguist Richard Robert Jones, or Dic Aberdaron, reputed to have mastered fourteen languages through his constant consumption of books. His patron, William Roscoe, describes how ‘His clothing consisted of several coarse and ragged vestments, the spaces between which were filled with books, surrounding him in successive layers so that he was literally a walking library… Absorbed in his studies, he had continually a book in his hand’.

So whilst trying to work out if I am bibliomanic or bibliophilic, I started thinking about other eminent book enthusiasts and, either way, I’m in good company! John Dee, the Elizabethan scientist and astrological advisor to Elizabeth I, we know was an avid accumulator of books, amassing one of the largest private libraries during the 16th century. Sadly, most of his collection was dispersed or stolen during his own lifetime, but Special Collections is fortunate to hold his copy of Thomas Aquinas’s Summa contra gen[t]iles . Naturally, Dee was bereft at the loss, and we get a sense of his deep devotion to books from his dreams. In one, which he recorded in his diary, he ‘dremed that I was deade… and … the Lord Thresoror was com to my howse to burn my bokes’. On August the 6th, 1597, Dee relates how:

‘On this night I had the vision … of many bokes in my dreame, and among the rest was one great volume thik in large quarto, new printed, on the first page whereof as a title in great letters was printed ‘Notus in Judaea Deus’. Many other bokes me-thowght I saw new printed, of very strange arguments’.

He too encountered an eight-legged beast, writing on the 2 of September: ‘the spider at ten of the clock at night suddenly on my desk, … a most rare one in bygnes and length of feet’. You know you’re in trouble when you can see their feet! I truly sympathise Dr Dee, on both counts.

And what about our very own Enoch Salisbury? His hunger for book collecting began with a gift, an 1824 Welsh edition of Robinson Crusoe, and developed over the next sixty years into a compilation of over 13,000 works worthy of a national collection, a genuine prospect at that time.

Just some of the books in the Salisbury Library

In 1886, financial troubles forced Salisbury to sell his collection which was ingeniously acquired by Cardiff University thanks to the foresight of its Registrar Ivor James. In a letter to James, Salisbury outlines his ‘one hope… that the same public feeling which carried it away to Cardiff, may lead to its perfection… for the use of a National Library’. When the concept for a National Museum and Library for Wales was being considered, Cardiff was a serious contender, offering both the Salisbury Library and the collected works at Cardiff Public Library to be housed in a joint museum and library at Cathays Park.

The Public Library collection was also compiled through several worthy deposits made by keen collectors. David Lewis Wooding (1828 -1891) was one. A shopkeeper and keen book collector, his library contained over 5,000 volumes which he donated. Another collection incorporated was the Tonn library in 1891, which belonged to the Rees family of Llandovery. This consisted of 7,000 printed volumes and 100 manuscripts, and even the Cardiff coal owner John Cory purchased 67 incunabula which he too presented to the Library.

Nevertheless, Cardiff’s vision for a cultural institution was scuppered by another Victorian bibliomaniac, Sir John Williams. He had been buying whole collections for his own private library since the 1870s, and in 1898 struck literary gold when he acquired the Peniarth Manuscripts, which he donated to the proposed library in 1907, on condition that it be built at Aberystwyth. With nuggets like the Black Book of Carmarthen, the White Book of Rhydderch and the Book of Taliesin, Cardiff was inevitably outdone, for the library at least.

As fate would have it, Cardiff University now houses the Cardiff Rare Books alongside Salisbury’s Library, forming a unique collection of national interest which, over the years, has morphed from one compendium to another, each carrying their own unique story. These collections and subsequently, Special Collections, would not exist if it weren’t for Bibliomania. So the moral of this post is, whether you’re bibliomanic, bibliophilic, even arachnophobic, it matters not; there is always an exquisite method in a madness for books, as seen in Daniel Jubb’s Bookcase.

As a PhD student I took part in training workshops on handling rare books and curating exhibitions. In 2011, I was given the opportunity to work alongside Special Collections staff to curate a small exhibition on an aspect of my PhD research. I chose the topic, Healthy Reading, 1590-1690. Focusing on this aspect helped me to contextualise the early printing and language of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, the focus of my wider PhD research. I later presented on the exhibition and the play during a conference in Paris on ‘Shakespeare et les arts de la table’. My subsequent book chapter on the subject featured images from the Special Collections. I’m very grateful to the Special Collections’ staff, as their support was crucial for this work.

As a PhD student I took part in training workshops on handling rare books and curating exhibitions. In 2011, I was given the opportunity to work alongside Special Collections staff to curate a small exhibition on an aspect of my PhD research. I chose the topic, Healthy Reading, 1590-1690. Focusing on this aspect helped me to contextualise the early printing and language of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, the focus of my wider PhD research. I later presented on the exhibition and the play during a conference in Paris on ‘Shakespeare et les arts de la table’. My subsequent book chapter on the subject featured images from the Special Collections. I’m very grateful to the Special Collections’ staff, as their support was crucial for this work. During my research, I became interested in the work of John Taylor (1578-1653), self-titled ‘the Water Poet’. He was a larger-than-life figure who worked as a Thames waterman for much of his life. However, he also published a great deal and his work – ranging from political pamphlets to travel writing to nonsense verse – often includes interesting prefaces, paratexts and titles.

During my research, I became interested in the work of John Taylor (1578-1653), self-titled ‘the Water Poet’. He was a larger-than-life figure who worked as a Thames waterman for much of his life. However, he also published a great deal and his work – ranging from political pamphlets to travel writing to nonsense verse – often includes interesting prefaces, paratexts and titles. I have created a new online modern-spelling edition of Taylor’s journey around Wales, and this has been published on a dedicated John Taylor website alongside other resources, such as a Google map of the route. I have also produced a schools’ pack on Taylor’s account of Mid Wales. Pupils at Penglais School (Aberystwyth) have used this to consider Taylor’s account of their hometown and have produced visualisations of his journey that will feed into the project. I now plan to tweet his journey in real time. He set off, with his horse called Dun, from London on 13 July, travelling up through the Midlands to North Wales and then along the coast down to Tenby and across South Wales via Cardiff, arriving back to London in early September. During the trip he turned 74.

I have created a new online modern-spelling edition of Taylor’s journey around Wales, and this has been published on a dedicated John Taylor website alongside other resources, such as a Google map of the route. I have also produced a schools’ pack on Taylor’s account of Mid Wales. Pupils at Penglais School (Aberystwyth) have used this to consider Taylor’s account of their hometown and have produced visualisations of his journey that will feed into the project. I now plan to tweet his journey in real time. He set off, with his horse called Dun, from London on 13 July, travelling up through the Midlands to North Wales and then along the coast down to Tenby and across South Wales via Cardiff, arriving back to London in early September. During the trip he turned 74.