This post comes from Devin Mattlin and Joanne Hoppe, MSc Conservation Practice students at Cardiff University, and conservation volunteers at Glamorgan Archives. Both have been working on the Collingwood Archive conservation project as student conservators thanks to the generous support of the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust.

Earlier of this year we had the fantastic opportunity to help conserve a collection of diaries and sketchbooks from the Collingwood Archive held at Special Collections and Archives, Cardiff University. The Collingwoods were a world-famous family of remarkable artists, archaeologists, and writers from the Lake District. W. G. Collingwood was John Ruskin’s secretary and biographer, and a friend of Arthur Ransome, author of Swallows and Amazons and a suspected double agent. The archive spans 60 boxes and comprises a treasure trove of distinctive materials largely inaccessible to research and the public – thousands of letters and correspondence dating from the 18th century (including letters from E. M. Forster and Beatrix Potter), diaries, sketches, personal recipe books, photographs, illustrated story books and outstanding landscapes of the Lake District.

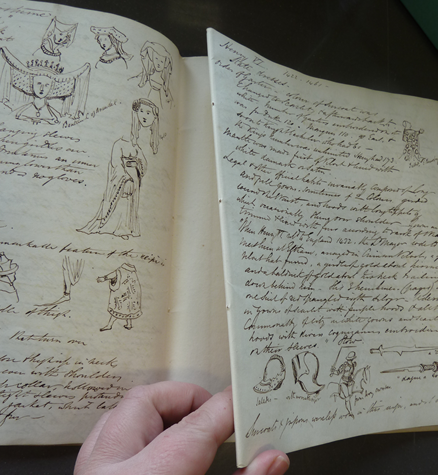

Study of English Costume, possibly by one of the Collingwood children, c. 19th century

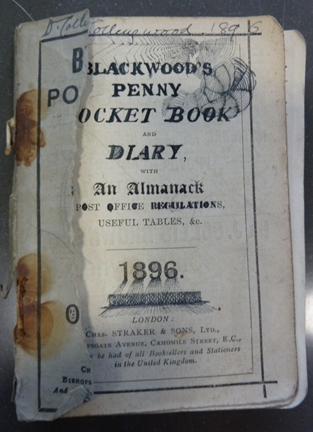

Diary of Dora Collingwood (1886-1964), before conservation work

In 2017, Cardiff University’s Special Collections and Archives was awarded their second successive grant from the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust to conserve key items from the archive, and we were delighted to be selected as part of our MSc Conservation Practice course to give them a hand. This was a great opportunity to learn new skills in paper conservation and to work with Lydia Stirling, an Accredited Conservation-Restorer, at Glamorgan Archives. The objects in question dated roughly from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries and consisted of several diaries, sketchbooks and a recipe book. The ultimate goal of the conservation work was to stabilise the objects for responsible and appropriate display, and allow access to researchers and the public in the Special Collections and Archives Reading Room.

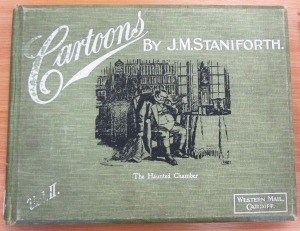

A Sketchbook of British Costume

One of the first objects we treated was a sketchbook of British Costume (c. 19th century) written in iron gall ink which, if left untreated, can rust through paper. This was confirmed with iron (II) indicator paper, as seen in the figure below – the paper turns a pink colour if iron (II) is present. After removing the dirt from the surface using a smoke sponge the pages were labelled in pencil and the threads used to originally sew the pages together were removed. To stabilise the iron gall ink, the pages were placed into four different water baths for 10 minutes each: water, calcium phytate, water, calcium bicarbonate. The calcium phytate reacts with the iron to form iron phytate compounds, which progressively slows down the iron corrosion. The calcium bicarbonate bath stabilises the paper by reducing its acidity, because as paper ages it becomes more acidic and thus more brittle. After the last water bath the wet pages were placed between blotter paper to dry. Once the pages had dried flat, the book was rebound using waxed linen thread.

Iron gall ink testing showing a positive result

Joanne stabilising the iron gall ink in various water baths

Collingwood Diaries

Many of the Collingwood diaries were falling apart and needed repairing due to the broken metal staples that were used to bind the pages together. To treat this type of damage we first removed the staples with a spatula, cleaned the surface and numbered the pages (once unbound, the sequence of the pages could be lost). Treatment of the holes involved shaping a piece of Japanese repair paper to the size of the hole by placing the original page on a light box with a sheet of plastic and the repair paper on top. The repair paper was then shaped to match the hole by using a needle and was then applied to the hole with wheat starch paste. A layer of thin Japanese tissue was then applied over the repair which was also treated with wheat starch paste to make it stronger. Tears in the paper were also repaired in the same way. Once all the repairs were done, the diaries were rebound, and the covers were reattached by adding mull (a type of bookbinding cloth) to the edge where the spine attaches and then adhering the repaired cover to that cloth strip.

- Surface cleaning the pages of the diary

- Devin rebinding the diaries onto specialist tapes

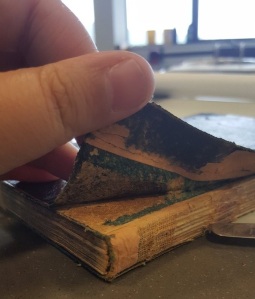

The boards are revealed under the original leather cover

However, one of the diaries could not be treated in the same way because it had a leather cover, unlike the others, which were paper. The spine on this diary had almost completely fallen off, so we made the decision to authentically restore it using new leather. First, the original cover was cut and lifted to expose the boards underneath. The repair leather was then shaved with knives to make it as thin as possible, so it would bend easily and fit under the original leather. Once the piece was sufficiently thin enough, it was saturated with wheat starch paste and then fitted onto the spine and under the lifted original leather. The original leather was then adhered on top.

Finished spine with the repair leather

The Collingwood Celebratory Conference

After we had completed the work we were delighted when the project team invited us to talk about our experience at the Collingwood Archive Celebratory Conference. Here we were given a fantastic platform to present our journey with the archive to a large audience of over 40 delegates from across the world, and share what conservation is and how archives are cared for. We were so grateful to the project team for this opportunity to communicate with many different heritage stakeholders, an essential skill that will be invaluable as we embark on our careers in conservation.

Devin and Joanne sharing their conservation experiences at the Collingwood Archive Celebratory Conference, April 2018

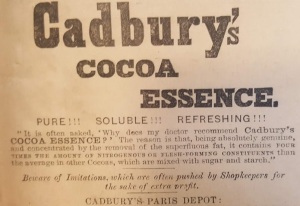

We would like to thank Lydia Sterling, Alan Vaughan Hughes and the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust for the opportunity to work with such a unique collection. Through this experience we practiced our paper conservation, bookbinding, and communication skills. It was also interesting to see beautiful artwork and to get a glimpse into the lives of the Collingwood family and the Victorian era. Our favourite items had to be an article pasted into the recipe book discussing how onions are so underrated, and a Cadbury’s advert from 1881!

- Article on the medicinal and cleaning properties of onions, from Edith Collngwood’s (1857-1928) recipe book, c. late 19th century

- Cadbury’s advert, from Edith’s recipe book, 1881

Passionate about archaeology as well as

Passionate about archaeology as well as