This guest post comes from Pip Bartlett, undergraduate in French and Italian in the School of Modern Languages at Cardiff University.

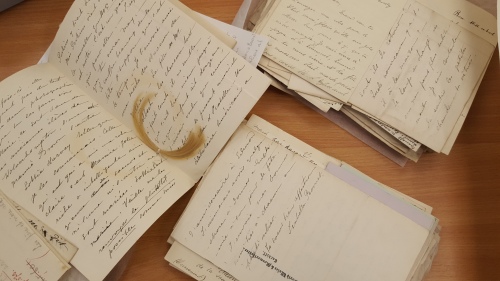

In this blog post, I will be sharing some of my discoveries about the Barbier family and their involvement in the First World War. As mentioned in my previous post, the Barbier archive contains several boxes of letters, organised into date order. Five of the grey boxes (1914, 1915, 1916, 1917 and 1918) contain correspondence between the family during the war years. So far, I have catalogued boxes 1914, 1915 and 1918, which have revealed information about the family’s activities, feelings and experiences at the time. I also used two of the booklets created by the previous owner (‘Barbier Voices from the Great War’ Parts 1 & 2) to support any findings I made; they contain very detailed information about each family member’s war experience, as well as including photographs and extracts from diaries.

According to ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’, prior to the outbreak of war all four of the Barbier brothers had well-established careers; Paul E A. Barbier had been Professor of French at the University of Leeds since 1903, Edmond was the assistant examiner in oral and written French to the Central Welsh Board, Georges was the manager of coal firm ‘Messrs Instone’ and Jules, a civil engineer in North America. Because of their French Nationality, the brothers had completed military service with the French Army well before the war (Paul completed his in 1889), making them no strangers to a military environment. According to the booklet, in August 1914 all four men, along with their brother-in-law Raoul Vaillant de Guélis (married to their sister Marie) were called up by the French state and sent to France.

According to ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’, prior to the outbreak of war all four of the Barbier brothers had well-established careers; Paul E A. Barbier had been Professor of French at the University of Leeds since 1903, Edmond was the assistant examiner in oral and written French to the Central Welsh Board, Georges was the manager of coal firm ‘Messrs Instone’ and Jules, a civil engineer in North America. Because of their French Nationality, the brothers had completed military service with the French Army well before the war (Paul completed his in 1889), making them no strangers to a military environment. According to the booklet, in August 1914 all four men, along with their brother-in-law Raoul Vaillant de Guélis (married to their sister Marie) were called up by the French state and sent to France.

Due to their French-English bilingualism, both Paul and Edmond were mobilised as interpreters for the British Expeditionary Forces. I am unsure if they were seconded from the French army – something I would like to ask the previous owner about in our interview.

Jules and Georges remained ‘poilus’ (ordinary field soldiers for the French army). Much of the archive from the war years is dedicated to correspondence from Paul E. A. Barbier (or Paul Barbier Fils, as in son, as he is known) to his wife Cécile. From what I have grasped after reading his letters, it seems Paul Barbier Fils had a reasonably ‘comfortable’ wartime experience; that is to say, he regularly talks of eating well and playing bridge with his brother Edmond. In numerous letters, he says he is in ‘good health and spirits’ and regularly returns to the UK on leave, which he documents. According to the letters in the archive, Paul Barbier Fils also remained in close contact with his colleagues at the University of Leeds. For example, there are letters from the Vice Chancellor of the university who asks for Paul’s opinion on various university matters. There is even a letter to Paul dated 29th June 1915 from the Vice Chancellor who says he has been in contact with the French Embassy in London attempting to release Paul from the army, unfortunately without success.

Jules and Georges remained ‘poilus’ (ordinary field soldiers for the French army). Much of the archive from the war years is dedicated to correspondence from Paul E. A. Barbier (or Paul Barbier Fils, as in son, as he is known) to his wife Cécile. From what I have grasped after reading his letters, it seems Paul Barbier Fils had a reasonably ‘comfortable’ wartime experience; that is to say, he regularly talks of eating well and playing bridge with his brother Edmond. In numerous letters, he says he is in ‘good health and spirits’ and regularly returns to the UK on leave, which he documents. According to the letters in the archive, Paul Barbier Fils also remained in close contact with his colleagues at the University of Leeds. For example, there are letters from the Vice Chancellor of the university who asks for Paul’s opinion on various university matters. There is even a letter to Paul dated 29th June 1915 from the Vice Chancellor who says he has been in contact with the French Embassy in London attempting to release Paul from the army, unfortunately without success.

I also found letters to Cécile Barbier from wives of other University staff whose husbands were at the front. Cécile served on a committee in Leeds which regularly sent parcels and gifts to University employees in France. Despite his relatively positive account of his wartime experiences in France, some of Paul’s letters to his wife are less cheerful and according to ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 2’, in May 1917 he writes ‘I start writing poetry again […] when I am overcome by sadness’, and in June ‘my intellectual life is a waste land. I long to talk to beings less deadly dull than those around me’. A year later in March 1918 he even says, ‘I am an exile, I am atrociously bored’. To fight these feelings of boredom, Paul evidently focused on his hobbies and interests. Ever the lexicographer (that is, a person who compiles dictionaries, an occupation that was linked to his academic preoccupations), Paul Barbier Fils became fascinated with the local dialect of the region in which he was stationed. He even compiled a dictionary of the dialect entitled ‘Lexique du Patois d’Erquinghem-Lys’, which was later published posthumously in 1980 by the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, France.

Georges Barbier, on the other hand, seemed to have had the most difficult war experience out of the family members who went to the Front. In 1916 he returned to London from the front due to illness to work for the Coal Board. In letters to his brothers and mother, he talks of suffering from night-blindness and having very little food, if any. His wife Nan died a few years later, leaving him a widower with two children. Fortunately, the three other brothers who remained in France survived, and in 1919 were demobilised from the army, returning to their peacetime lives in Cardiff. Their brother-in-law, Raoul Vaillant de Guélis was not so fortunate and died of pneumonia in 1916. His wife Marie never remarried and raised her two children along with those of her brother George after his death in 1921. One of her children, Jacques Vaillant de Guélis became a Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, an undercover spy who carried out missions in France during the Second World War. I do not know much about his life yet, but I am excited to discover more over the upcoming weeks.

Georges Barbier, on the other hand, seemed to have had the most difficult war experience out of the family members who went to the Front. In 1916 he returned to London from the front due to illness to work for the Coal Board. In letters to his brothers and mother, he talks of suffering from night-blindness and having very little food, if any. His wife Nan died a few years later, leaving him a widower with two children. Fortunately, the three other brothers who remained in France survived, and in 1919 were demobilised from the army, returning to their peacetime lives in Cardiff. Their brother-in-law, Raoul Vaillant de Guélis was not so fortunate and died of pneumonia in 1916. His wife Marie never remarried and raised her two children along with those of her brother George after his death in 1921. One of her children, Jacques Vaillant de Guélis became a Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, an undercover spy who carried out missions in France during the Second World War. I do not know much about his life yet, but I am excited to discover more over the upcoming weeks.

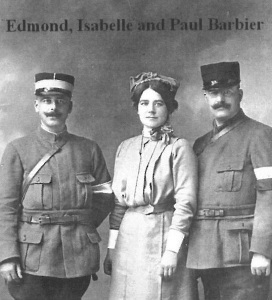

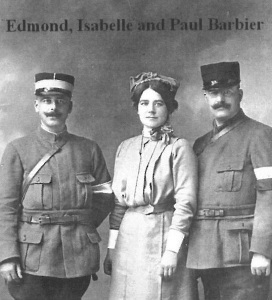

Finally, while the brothers were at the Front, their younger sister, Isabelle Barbier, spent time in France as a nurse during WW1. Unlike her brothers, there is little correspondence from Isabelle during the war years throughout the archive, but ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’ gives detailed accounts about her time as an assistant to Dame Maud McCarthy, Matron in Chief to the British Expeditionary Forces. On page 7 of the booklet, there is a lovely picture of Isabelle with her brothers Edmond and Paul, as well as a picture of her in uniform wearing the Royal Red Cross – presumably she was awarded this, but I am unsure when. It is something I would like to find more about when I speak to the previous owner of the archive. All in all, the archive offers insights into the wartime experiences of this remarkable family and it has been particularly fascinating to discover how Paul Barbier Fils continued his interests and worked remotely with the University of Leeds. I hope the former owner is able to answer some of the questions which I have raised, as I feel there are some interesting pointers for future research.

Finally, while the brothers were at the Front, their younger sister, Isabelle Barbier, spent time in France as a nurse during WW1. Unlike her brothers, there is little correspondence from Isabelle during the war years throughout the archive, but ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’ gives detailed accounts about her time as an assistant to Dame Maud McCarthy, Matron in Chief to the British Expeditionary Forces. On page 7 of the booklet, there is a lovely picture of Isabelle with her brothers Edmond and Paul, as well as a picture of her in uniform wearing the Royal Red Cross – presumably she was awarded this, but I am unsure when. It is something I would like to find more about when I speak to the previous owner of the archive. All in all, the archive offers insights into the wartime experiences of this remarkable family and it has been particularly fascinating to discover how Paul Barbier Fils continued his interests and worked remotely with the University of Leeds. I hope the former owner is able to answer some of the questions which I have raised, as I feel there are some interesting pointers for future research.

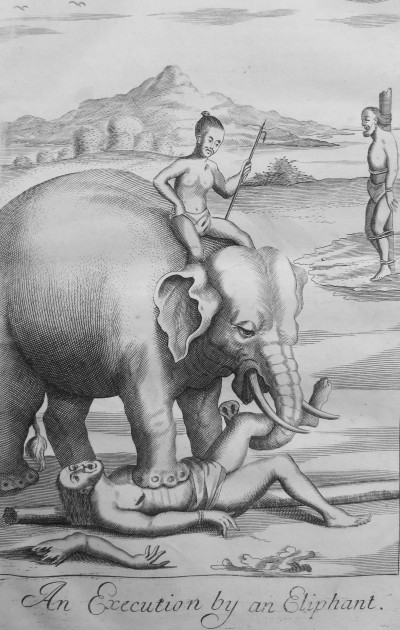

As a PhD student I took part in training workshops on handling rare books and curating exhibitions. In 2011, I was given the opportunity to work alongside Special Collections staff to curate a small exhibition on an aspect of my PhD research. I chose the topic, Healthy Reading, 1590-1690. Focusing on this aspect helped me to contextualise the early printing and language of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, the focus of my wider PhD research. I later presented on the exhibition and the play during a conference in Paris on ‘Shakespeare et les arts de la table’. My subsequent book chapter on the subject featured images from the Special Collections. I’m very grateful to the Special Collections’ staff, as their support was crucial for this work.

As a PhD student I took part in training workshops on handling rare books and curating exhibitions. In 2011, I was given the opportunity to work alongside Special Collections staff to curate a small exhibition on an aspect of my PhD research. I chose the topic, Healthy Reading, 1590-1690. Focusing on this aspect helped me to contextualise the early printing and language of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, the focus of my wider PhD research. I later presented on the exhibition and the play during a conference in Paris on ‘Shakespeare et les arts de la table’. My subsequent book chapter on the subject featured images from the Special Collections. I’m very grateful to the Special Collections’ staff, as their support was crucial for this work. During my research, I became interested in the work of John Taylor (1578-1653), self-titled ‘the Water Poet’. He was a larger-than-life figure who worked as a Thames waterman for much of his life. However, he also published a great deal and his work – ranging from political pamphlets to travel writing to nonsense verse – often includes interesting prefaces, paratexts and titles.

During my research, I became interested in the work of John Taylor (1578-1653), self-titled ‘the Water Poet’. He was a larger-than-life figure who worked as a Thames waterman for much of his life. However, he also published a great deal and his work – ranging from political pamphlets to travel writing to nonsense verse – often includes interesting prefaces, paratexts and titles. I have created a new online modern-spelling edition of Taylor’s journey around Wales, and this has been published on a dedicated John Taylor website alongside other resources, such as a Google map of the route. I have also produced a schools’ pack on Taylor’s account of Mid Wales. Pupils at Penglais School (Aberystwyth) have used this to consider Taylor’s account of their hometown and have produced visualisations of his journey that will feed into the project. I now plan to tweet his journey in real time. He set off, with his horse called Dun, from London on 13 July, travelling up through the Midlands to North Wales and then along the coast down to Tenby and across South Wales via Cardiff, arriving back to London in early September. During the trip he turned 74.

I have created a new online modern-spelling edition of Taylor’s journey around Wales, and this has been published on a dedicated John Taylor website alongside other resources, such as a Google map of the route. I have also produced a schools’ pack on Taylor’s account of Mid Wales. Pupils at Penglais School (Aberystwyth) have used this to consider Taylor’s account of their hometown and have produced visualisations of his journey that will feed into the project. I now plan to tweet his journey in real time. He set off, with his horse called Dun, from London on 13 July, travelling up through the Midlands to North Wales and then along the coast down to Tenby and across South Wales via Cardiff, arriving back to London in early September. During the trip he turned 74.