When I set out to learn more about the provenance of one of our rare books, I could not have predicted the twists and turns that would lead directly to the library of one of the world’s greatest scientists.  Our copy of John Browne’s Myographia nova, or A graphical description of all the muscles in humane body was published in London in 1698. When it appeared on my desk for cataloguing I expected to find some interesting (and gory) anatomical engravings and not much else. I opened the book to reveal an unusual bookplate bearing only a Latin motto, “Philosophemur”, with no indication of the previous owner’s name. On closer examination it was apparent that this bookplate had been pasted directly over an earlier, smaller bookplate, obscuring it completely. There were two handwritten shelfmarks, one at the top left of the page, “732_24”, and one at the foot of the bookplate which reads “Case V. E.7. Barnsley.”

Our copy of John Browne’s Myographia nova, or A graphical description of all the muscles in humane body was published in London in 1698. When it appeared on my desk for cataloguing I expected to find some interesting (and gory) anatomical engravings and not much else. I opened the book to reveal an unusual bookplate bearing only a Latin motto, “Philosophemur”, with no indication of the previous owner’s name. On closer examination it was apparent that this bookplate had been pasted directly over an earlier, smaller bookplate, obscuring it completely. There were two handwritten shelfmarks, one at the top left of the page, “732_24”, and one at the foot of the bookplate which reads “Case V. E.7. Barnsley.”

The “Philosophemur” bookplate with the Barnsley Park shelfmark

Intrigued by this mysterious provenance, I set out to do some detective work in the hope of identifying some of these previous owners. After a little searching I was able to determine that the “Philosophemur” bookplate originally belonged to a Dr. James Musgrave, Rector of Chinnor, near Thame in Oxfordshire. On his death, he left his library to his son, the eighth baronet Musgrave and owner of Barnsley Park, Gloucestershire, and the books were removed to the library there in 1778. Baronet Musgrave evidently did not feel the need to affix his own bookplates, but the books were recatalogued on arrival and the Barnsley shelfmark added to each volume.

The text of the Huggins bookplate is just visible through the Musgrave plate

More detective work revealed that James Musgrave originally purchased his library from his predecessor at Chinnor, a man called Charles Huggins, and it is his bookplate which is just visible beneath Musgrave’s. Although the plate is covered, the words “… in Com. Oxon” can be made out and Charles Huggins is known to have used a bookplate displaying the Huggins coat of arms with “Revd. Carols. Huggins, Rector Chinner in Com. Oxon” beneath. Huggins received his books from his father, John Huggins, Warden of the Fleet Prison, who in turn purchased the library from the estate of his neighbour, Sir Isaac Newton.

Godfrey Kneller’s portrait of Isaac Newton in 1689

Apparently when Sir Isaac Newton died in 1727, he neglected to leave a will behind and his house and all his possessions, including his extensive library, were put up for auction. John Huggins purchased the books for £300 and a list was made referring to 969 books by name, with others grouped together under miscellaneous headings (an inventory of Newton’s house recorded a total of 1,896 volumes in the library). The Musgrave library was catalogued in 1760 and our book makes an appearance as “Browne’s On the Muscles, with Cutts, 1698”. Presence on the Huggins list is commonly taken as proof that a book belonged to Newton. The Musgrave catalogue is considered less reliable as it also includes later books added by the family, however the existence of both the Huggins and Musgrave bookplates and the two shelfmarks can, according to John Harrison’s (1976) advice on identification, be taken as strong evidence that our book once stood on Newton’s shelves.

Front pastedown of the book with the bookplates and shelfmarks

The later history of Newton’s library is an extraordinary one. As late as 1775 it was known that Musgrave owned Newton’s books, as visitors wrote about travelling to view the library, but after 1778, when Musgrave died and the books were transferred to Barnsley Park, the connection to the scientist appears to have been lost. Until 1920 it was thought that Newton’s library had simply vanished. In that year the Musgrave family decided to sell their house at Thame Park, and the “Philosophemur” books were sent over from Barnsley Park to be included in the sale. Newton’s books were sold in bundles with no indication of their importance and for a fraction of their true worth. It has long been believed that many of these books ended up in the United States, though it was feared that many more were sent to the mills for pulping, and many are still unaccounted for.

Newton in later life, by James Thornhill

Happily, not all of Newton’s books were scattered and lost in 1920. After the auction a further 858 volumes from the great scientist’s library were discovered at Barnsley Park, secreted throughout the house in cupboards and closets. This time the provenance was firmly established by Richard de Villamil and in 1943 the remaining books were purchased for the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, where Newton did so much of his remarkable work.

References:

De Villamil, R. “The tragedy of Sir Isaac Newton’s library,” The Bookman, March, 1927, 303-304

Harrison, John. “Newton’s library: Identifying the books,” Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume XXIV, October, 1976. No. 4, 395-406

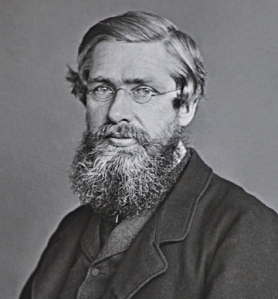

2013 marks the centenary of the death of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), a naturalist and biologist who was born in Llanbadock near Usk, Monmouthshire. In the last hundred years he has been mainly overshadowed by his contemporary Charles Darwin; but with the anniversary of his death, his work has started to be commemorated recently in TV programmes. The most recent was broadcast on BBc2 on Sunday 21st April 2013, and featured the comedian Bill Bailey heading to Indonesia to follow in the footsteps of Wallace, who collected thousands of specimens there.

2013 marks the centenary of the death of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), a naturalist and biologist who was born in Llanbadock near Usk, Monmouthshire. In the last hundred years he has been mainly overshadowed by his contemporary Charles Darwin; but with the anniversary of his death, his work has started to be commemorated recently in TV programmes. The most recent was broadcast on BBc2 on Sunday 21st April 2013, and featured the comedian Bill Bailey heading to Indonesia to follow in the footsteps of Wallace, who collected thousands of specimens there.