It was a dark and stormy afternoon in Special Collections & Archives. I was sitting in my office, cataloguing a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, when Lisa, our Assistant Librarian, tapped at my office door. ‘I think maybe there’s an error in the catalogue,’ she said.

When the Cardiff Rare Books collection came to Cardiff University in 2010, we’d drawn up a bare-bones inventory, knowing that it would be several years before the collection could be fully catalogued. Lisa had been looking through the collection inventory to look for uncatalogued books that might be useful for a resource guide on Witchcraft. ‘The inventory says this book was published in 1681, but the catalogue record says 1685,’ she observed as she showed me the two conflicting records.

Being a cataloguer and somewhat inclined to obsessive-compulsive behaviour, I couldn’t allow such an egregious error to remain in our records, so I went to the stacks to investigate. Stretching to reach the top-most shelf, I spotted the title in question: William Lilly’s Merlini Anglici ephemeris: or, Astrological judgments for the year 1685… with the 1681 issue, uncatalogued, sitting next to it on the shelf—both records had been correct, but incomplete! Alongside these almanacs I noticed several other volumes of William Lilly’s astrological writings. Thinking they might be useful for the resource guide, I brought the lot of them back to my office for cataloguing.

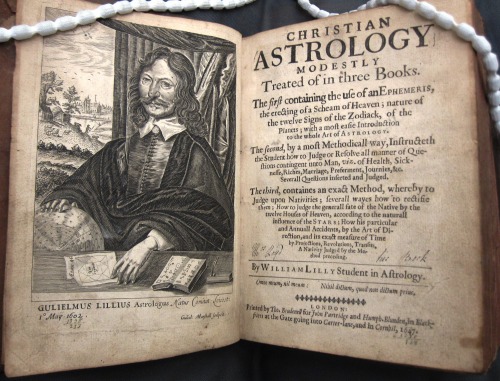

A selection of astrological books by William Lilly, from the Cardiff Rare Books Collection.

A contemporary of John Dee and Nicholas Culpeper, William Lilly began his life as the son of a yeoman farmer in Leicestershire. He worked for seven years as a servant in London before marrying his former master’s widow when he was just 25 years old. Now a man of leisure, he spent his time studying astrology. From 1647 to 1682, he published a series of astrological almanacs which brought him both popularity and scandal. By 1649, sales of his almanacs had reached nearly 30,000 copies and by the 1650s, they were being translated into Dutch, German, Swedish, and Danish. At he same time, however, he made many enemies by predicting on astrological grounds the downfall of the Stuart monarchy, while also criticizing both parliament and the Presbyterians.

Among the volumes I’d picked up for cataloguing was a first edition of Christian astrology modestly treated of in three books (London, 1647), Lilly’s most comprehensive work. An amalgamation of 228 earlier texts, Christian astrology contains 832 pages of instruction on reading the stars and planets and their influence on everything from the physical characteristics and likely fortunes of unborn children, to international politics. The work is significant because it was the first astrological instruction book to be published in English rather than Latin, making it accessible to a middle-class audience.

After carefully transcribing the book’s bibliographical details, I began to describe the unique attributes our particular copy: binding and marginalia. I spotted inscriptions in at least four different hands, ranging across three centuries. I deciphered and recorded them in the catalogue record as best I could, and then brought the volume over to Lisa, thinking she might find them interesting.

Inscriptions, dating between the 17th and 19th centuries, on the front endpaper of William Lilly’s Christian astrology (London, 1647)

* * *

‘Is that the “Old Prophet’s” signature?’ I exclaimed, at which point, the lights in the office flickered. I had a sixth-sense (those of us who work with special collections often get this!) that this was the signature of the Welsh Independent Minister and author, Edmund Jones (1702-1793).

An intriguing figure in eighteenth-century Wales, he was a passionate Calvinist connected with the vicinity of Pontypool and Monmouthshire, where he regularly preached during the 1730s. Sympathetic to the growing Methodist movement, characterized by a more heartfelt, experiential form of religion, it was Jones who encouraged Howell Harris to preach in Monmouthshire for the first time in 1738.

Certainly, his diaries record a dedicated schedule where he travelled and preached extensively, delivering 104 sermons in the year 1731. Almost fifty years later, in 1778, he took a ‘tour through Monmouth [and] Wales … to Caerphilly’. Although not traditionally educated, his autobiography reveals how he was a ‘great lover of books, buying and borrowing as much as he could’. One such book it seemed, appeared to be our copy of Lilly’s Christian astrology.

In order to confirm my suspicions, we needed to compare this signature with some known examples of Jones’s handwriting. Fortunately, the National Library of Wales holds Jones’s diaries, saved from the final destination of being used as wrapping paper in a Pontypool shop. Thanks to the help of their Manuscript Librarian, these journals not only reveal a script eerily similar to our sample, they also include a list of books that Jones acquired …

And yes! No need to consult the stars on this one, for Lily’s Astrology is clearly recorded at the bottom of the page.

A page from Edmund Jones’ diary for the year 1768, listing the books that Jones acquired that year. Held by the National Library of Wales (NLW MS 7025A).

So not only does Special Collections hold Edmund Jones’s personal, annotated copy of Lilly’s Astrology, but this discovery reveals Jones’s more mystical side.

Known as the ‘Old Prophet’ due to his apparent gift of prophecy and ability to foretell future events, he was also a firm believer in witchcraft and the supernatural. His interest in books was not confined to collecting, for he published a number of works, including A Relation of Apparitions of Spirits which comprised a collection of supernatural experiences and spiritual encounters designed to ‘prevent a kind of infidelity … the denial of the being of Spirits and Apparitions, which hath a tendency to irreligion’.

As the seventeenth century drew to a close, a slight change of attitude towards the beliefs in apparitions and witchcraft, is evident. Atheism now posed a greater threat than popery (Roman Catholicism), and works composed around this time were directed at countering this new danger.

Joseph Glanvill’s Sadducisimus Triumphatus, for example, provides ‘full and plain evidence concerning witches and apparitions’. To deny the existence of the spirit, he argues, ‘is quite to destroy the credit of all human testimony’. Bovet’s Pandaemonium, or the devil’s cloyster, is aimed at ‘proving the existence of witches and spirits’, for ‘there can be no apprehensions … from the attacks of the … Sadducees’. For Richard Baxter, a belief in spirits was a means to salvation since through faith in the world of spirits, the ‘saving’ knowledge of God could be obtained.

It is in this context that Jones collected Relations of Apparitions which include fairy encounters and apparitions such as corpse candles and phantom funerals. For example, a ‘Mr. E. W.’ confirmed in a letter to Jones that saw the fairies as a company of dancers in the middle of the field, while an innkeeper from Llangynwyd Fawr saw them with speckled clothes of white and red, as they tried to entice him a while he lay in bed. Another gentleman also told Jones how ‘the resemblance of a young child … and also of a big man’ appeared to him. As he looked on, ‘the child seemed to vanish into nothing’. Not long after the encounter, Jones notes, the child of the man who witnessed the apparition sickened and died, as did he not long after his daughter was buried.

The phantom funeral or Toili, could manifest itself as a mournful sound, the cyhyraeth. Noises associated with the funeral procession or service, or the dismal cries of the Cŵn Annwn (Hell Hounds), inevitably signalled death. Thomas Phillips heard the cries of these spiritual dogs prior to the death of a woman in his parish of Trelech. In Ystradgynlais, two women heard someone singing psalms. The voice was that of John Williams, who sang the psalms at a later Dissenting meeting and was indeed ‘buried’ a few days after. Faced with such great sums of truth, Jones challenges, ‘who … can deny the reality of Apparitions of Spirits?’

Indeed, and here at Special Collections we are well aware of the ghosts of owners past that we sometimes encounter amongst the aged pages of our rare books. Like Jones’s unique accounts of the supernatural experiences of ordinary Welsh men and women, these rare books occasionally reveal the spectre of a bygone reader and their occult interests. So the moral of this post is to beware! For you can never predict what you’ll find between the pages of a rare book, even one on predictions.