Our doors may be closed, but whether from our attics, bedrooms, or desks-under-the-stairs, we are still here to support your learning, creativity, and well-being during these unprecedented times.

No rest for the wicked, nor the self-isolated: we’ve been busy preparing a guide to free, digital primary sources from heritage organisations all over the world over on our website. But as well as the big hitters, there are a whole host of blogs and online research projects for those of you who can’t currently acquire all the sources you may need for your studies (or are just plain curious or bored).

No rest for the wicked, nor the self-isolated: we’ve been busy preparing a guide to free, digital primary sources from heritage organisations all over the world over on our website. But as well as the big hitters, there are a whole host of blogs and online research projects for those of you who can’t currently acquire all the sources you may need for your studies (or are just plain curious or bored).

Here’s a list of just a few that may help bridge that gap:

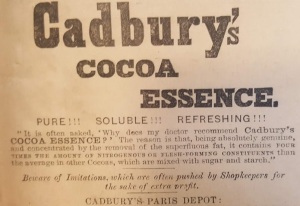

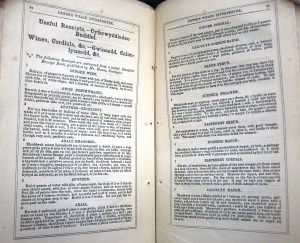

The Recipes Project: Food, Magic, Art, Science, and Medicine

Feeling peckish? I for one have a more severe case of the munchies now that I’m consigned to binge-reading and Netflixing for the foreseeable future, and this site is an excellent way to satiate it without heading out for non-essential M&Ms. As the website states, it’s an international collaborative research project where scholars interested in the history of recipes explore the weird and wonderful ways that recipes – for magical charms, cosmetics, food, and remedies – offer a unique window into the past. It’s full of interesting posts, sources, and more importantly for those growling stomachs – recipes, so most definitely worth a look, especially, and there’s no judgement here – we’re all getting by as best we can – this medieval Russian hangover cure. Check out their Additional Resources too.

Dr Alun Withey

What this fabulous and funky historian of early modern medicine and social history does not know about the strange, superb, and hairy aspects of early medical practices and facial grooming, quite frankly, is not worth shaving for. Packed with fascinating posts spanning a huge array of themes that encompass our medical and social past, from ‘polite’ hands, roasted mice, pigeon cures to bloodletting and beard sculpting, you could lose yourself for hours in Dr Withey’s blog. There’s even an abusive parrot in there. Well, I guess we’ll all be ‘talking to the cowing birds’ before long.

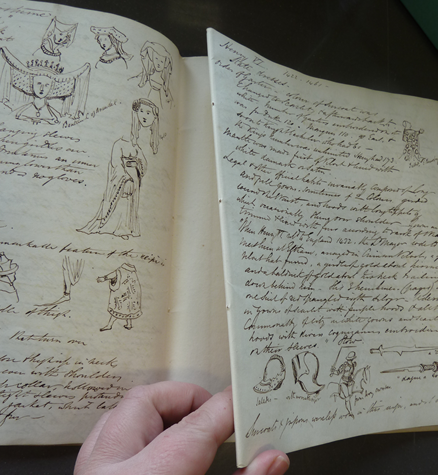

Medieval Manuscripts blog

When in doubt, check out the British Library’s website – this blog on their medieval and earlier manuscripts is well worth a look. As well as publicising their digitisation projects and other activities, this blog contains a wealth of interesting posts on the people, collections, and details relating to their unique manuscript collection. From digitised Middle English manuscripts to Greek papyri, this will satisfy all your manuscript needs. In addition, its generous visual content and links to other related materials could give you the illusion that you are actually sitting in the British Library, manuscript rather than TV remote to hand. Medieval Manuscripts is the perfect way to illuminate and chill!

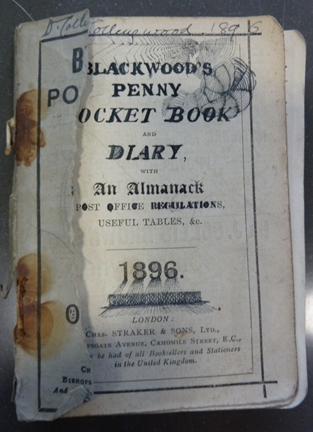

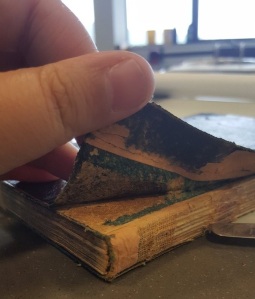

15cBOOKTRADE

This completed project on the history of the book trade during the fifteenth century by Oxford University considers the thousands of surviving books from the invention of modern printing by Gutenberg in c. 1450, to 1500 as material and unique documentary evidence of one of the most important developments in our cultural history. With the aid of a rare, unpublished ledger of a Venetian bookseller in the 1480s, which records the sale and prices of some of 25,000 printed books, the project addresses five fundamental questions relating to the introduction of printing in the West: Distribution, use, and reading practices; The books’ contemporary market value; The transmission and dissemination of the texts; The circulation and use of illustrations; and Visualisation – a database that helps us to visualise the circulation of the books and the texts they contain, over space and time. How amazing is that? Everything you need to know, and see, about the very start of the printing and book trade, without having to leave your house! Bonus points during these current times, and an absolute hat-trick for anyone interested in the history of literacy, printing, and the book trade in the second half of the fifteenth century.

This completed project on the history of the book trade during the fifteenth century by Oxford University considers the thousands of surviving books from the invention of modern printing by Gutenberg in c. 1450, to 1500 as material and unique documentary evidence of one of the most important developments in our cultural history. With the aid of a rare, unpublished ledger of a Venetian bookseller in the 1480s, which records the sale and prices of some of 25,000 printed books, the project addresses five fundamental questions relating to the introduction of printing in the West: Distribution, use, and reading practices; The books’ contemporary market value; The transmission and dissemination of the texts; The circulation and use of illustrations; and Visualisation – a database that helps us to visualise the circulation of the books and the texts they contain, over space and time. How amazing is that? Everything you need to know, and see, about the very start of the printing and book trade, without having to leave your house! Bonus points during these current times, and an absolute hat-trick for anyone interested in the history of literacy, printing, and the book trade in the second half of the fifteenth century.

Curious Travellers

For all of us in need of a bit of virtual travelling, we can explore Snowdon and any other eighteenth-century Welsh tourist hot spot without worrying about social distancing, by simply visiting this website. This four-year AHRC-funded research project, launched in September 2014 and jointly run by the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies (CAWCS) and the University of Glasgow, looks at Romantic-period accounts of journeys into Wales and Scotland. The writings of the Welsh naturalist and antiquarian Thomas Pennant (1726-1798) provide the main focus, and a range of other materials will help satisfy any Welsh (and Scottish) wanderlust we may be harbouring during our home-stays.

There are some nifty, freely-available research tools, including a database of Pennant’s extensive and scattered correspondence, and a searchable online corpus of some 60 (previously unpublished!) Welsh and Scottish Tours. led by Dr Mary-Ann Constantine of the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies (CAWCS) and Professor Nigel Leask of the University of Glasgow, Curious Travellers goes well beyond your traditional Rough Guide.

On History

This blog provides access to all the news, articles and research from the Institute of Historical Research (IHR). Check out their reviews of the latest historical publications via the Reviews in History series; see all their open access initiatives and links to other blogs and resources such as the Royal Historical Society’s Historical Transactions Blog, and New Historical Perspectives – the latest book series for early career scholars; or read extracts from the Camden Society publications, some volumes of which are available through British History Online. BHO is a digital collection of over 1,280 volumes of primary and secondary sources on the history of Britain and Ireland primarily focusing on the years 1300-1800. All transcribed content on the site has now been made freely available online until 31 July 2020! There is plenty of online content, news, and historical features to keep you going for months.

This blog provides access to all the news, articles and research from the Institute of Historical Research (IHR). Check out their reviews of the latest historical publications via the Reviews in History series; see all their open access initiatives and links to other blogs and resources such as the Royal Historical Society’s Historical Transactions Blog, and New Historical Perspectives – the latest book series for early career scholars; or read extracts from the Camden Society publications, some volumes of which are available through British History Online. BHO is a digital collection of over 1,280 volumes of primary and secondary sources on the history of Britain and Ireland primarily focusing on the years 1300-1800. All transcribed content on the site has now been made freely available online until 31 July 2020! There is plenty of online content, news, and historical features to keep you going for months.

History Past and Present

The University of Nottingham has a series of lively and informative blogs written by students, staff and academics on a wide range of subjects across multiple disciplines. The Arts and Humanities section posts on a range of topics including popular culture, cultures, language and area studies, and even Bringing Vikings back to the East Midlands – hopefully they respect social distancing and anti-bac-wipe their axes on a regular basis! The History Past and Present blog offers a wide range of instructive and motivating posts on academic articles, publications, key historical events, themes and topics.

The University of Nottingham has a series of lively and informative blogs written by students, staff and academics on a wide range of subjects across multiple disciplines. The Arts and Humanities section posts on a range of topics including popular culture, cultures, language and area studies, and even Bringing Vikings back to the East Midlands – hopefully they respect social distancing and anti-bac-wipe their axes on a regular basis! The History Past and Present blog offers a wide range of instructive and motivating posts on academic articles, publications, key historical events, themes and topics.

So plenty to keep studious, curious, and jaded minds going throughout the current lockdown. Consider this your virtual-learning comfort blanket – and don’t forget to check out our new guide to digitised primary sources.

Until we see you again: stay indoors, stay safe, and read a blog – over and out!