Special Collections and Archives‘ latest exhibition, Tennyson’s Women, compares changing artistic approaches to illustrating the works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892).

It examines the visual depiction of female characters in the context of the Victorian medieval revival. Forgotten female illustrators, such as Eleanor Brickdale, Florence Harrison and Katherine Cameron, feature alongside more famous works by Gustave Doré, J. E. Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Mae arddangosfa ddiweddaraf Casgliadau Arbennig ac Archifau, Merched Tennyson, yn cymharu dulliau artistig newidiol i ddarlunio gwaith yr Arglwydd Tennyson (1809-1892).

Mae’n archwilio darluniad gweledol cymeriadau benywaidd yng nghyd-destun yr adfywiad canoloesol Fictoraidd. Mae darlunwyr benywaidd angof, gan gynnwys Eleanor Brickdale, Florence Harrison, Katherine Cameron a Violet Fane yn cael eu portreadu ochr yn ochr â gwaith mwy enwog gan Gustave Doré, J. E. Millais a Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Lady of Shalott / Y Feinir o Sialót

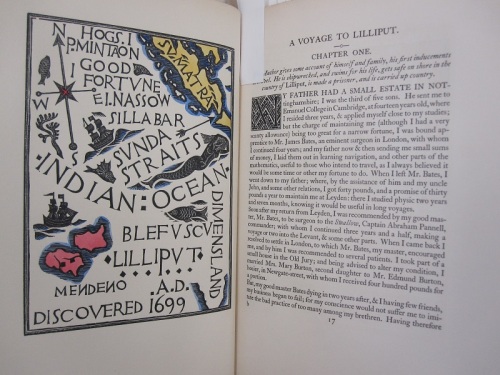

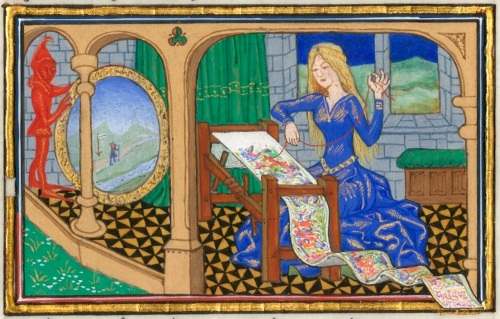

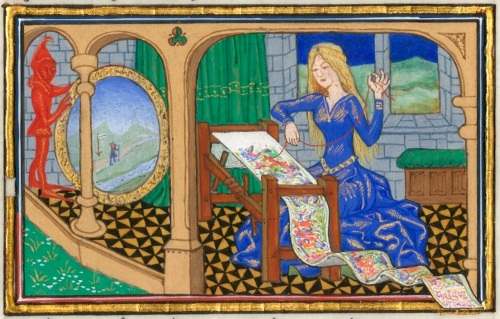

The Lady of Shalott inspired numerous artists, who were drawn to the story of a woman who commits a specifically visual crime by looking directly through a window. The illuminated manuscript represents the Lady of Shalott happily at work on her tapestry as she weaves the objects seen in the mirror’s reflections.

Bu’r Feinir o Sialót yn ysbrydoliaeth i nifer o ddarlunwyr a gafodd eu denu gan hanes menyw sy’n cyflawni trosedd weledol amlwg wrth edrych drwy ffenestr. Mae’r llawysgrif wedi’i oleuo yn cynrychioli Boneddiges Shalott yn fodlon ei byd yn gweithio ar dapestri wrth iddi blethu’r nwyddau sydd i’w gweld yn y drych.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Lady of Shalott, illuminated by Gilbert Pownall (c. 1910).

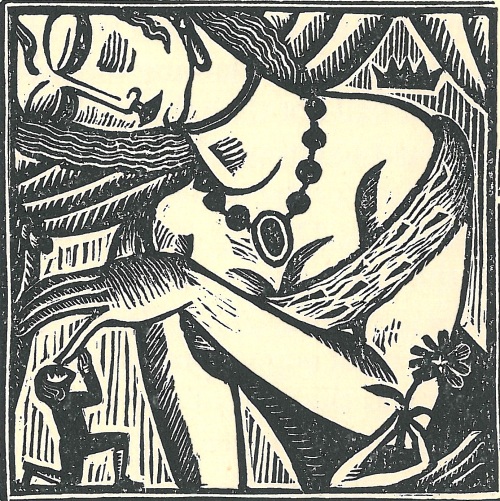

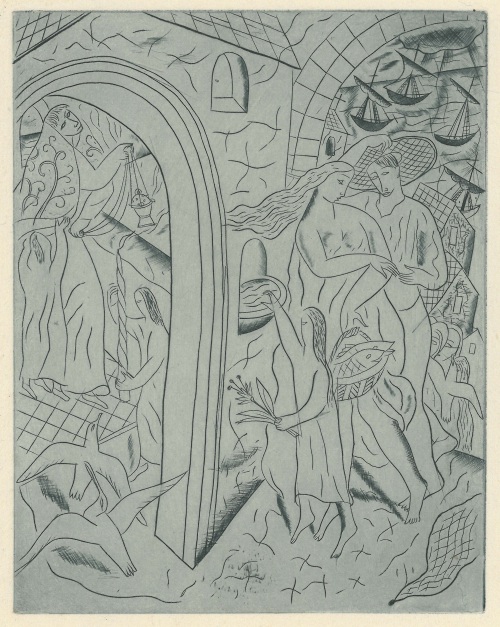

Most illustrations, however, focus on the moment of the curse when the Lady of Shalott leaves the loom and looks through the window at Lancelot.

Mae’r rhan fwyaf o ddarluniau, fodd bynnag, yn canolbwyntio ar olygfa’r felltith pan fo’r Feinir o Sialót yn gadael yr ystafell gan edrych drwy’r ffenestr ar Lawnslot.

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces through the room,

She saw the water-flower bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume:

She look’d down to Camelot.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Tennyson’s Dream of fair women and other poems, illustrated by Florence Harrison. London: Blackie, c. 1923. Image reproduced with the kind permission of the Florence Susan Harrison Estate.

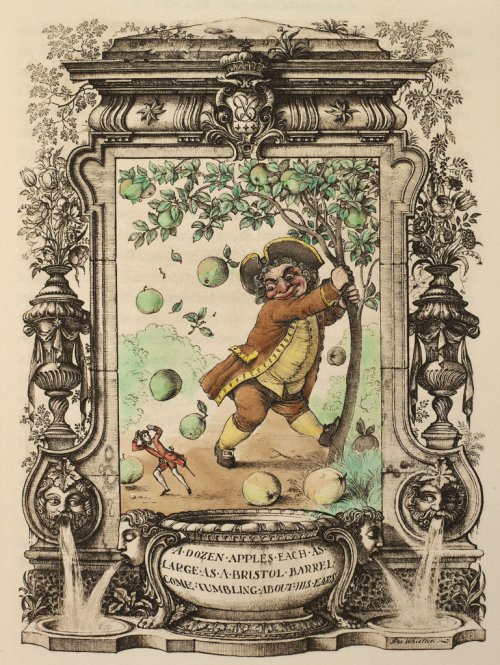

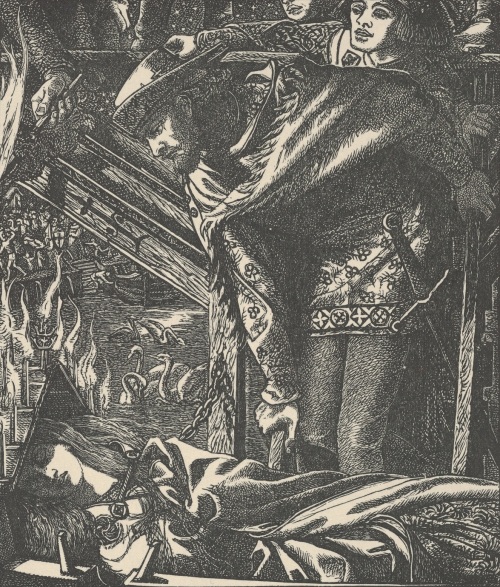

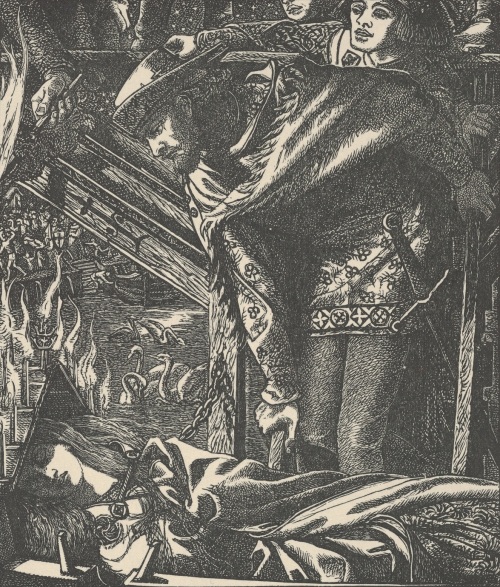

This moment is represented with dramatic force in William Holman Hunt’s illustration where the Lady of Shalott is tangled in the threads of the tapestry, her hair flying wildly across the picture. Tennyson objected to Hunt’s addition of these features, because they were not present in the text.

Dangosir yr olygfa hon gyda chryn rymuster yn narlun William Holman Hunt o’r Feinir o Sialót yn sownd yng nghlymau’r tapestri, a’i gwallt yn chwifio’n wyllt ar draws y llun. Nid oedd Tennyson yn cymeradwyo’r ychwanegiadau hyn gan nad oeddent yn y testun gwreiddiol.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.’

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Some poems by Alfred Lord Tennyson, illustrated by W. Holman Hunt et al. London: Freemantle & Co., 1901.

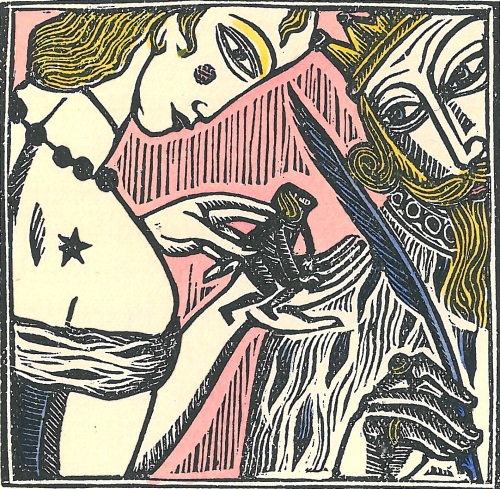

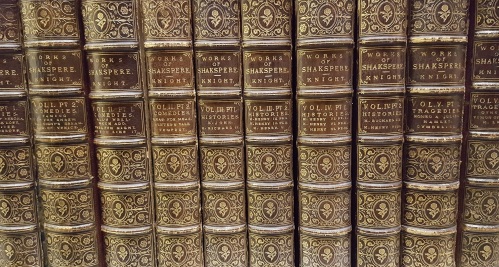

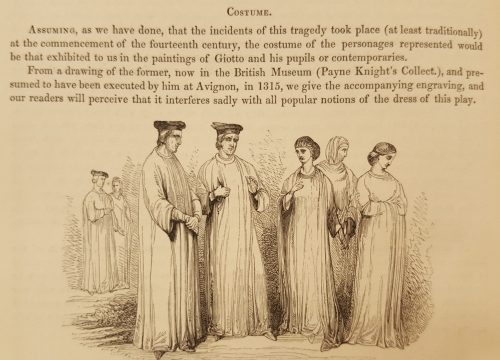

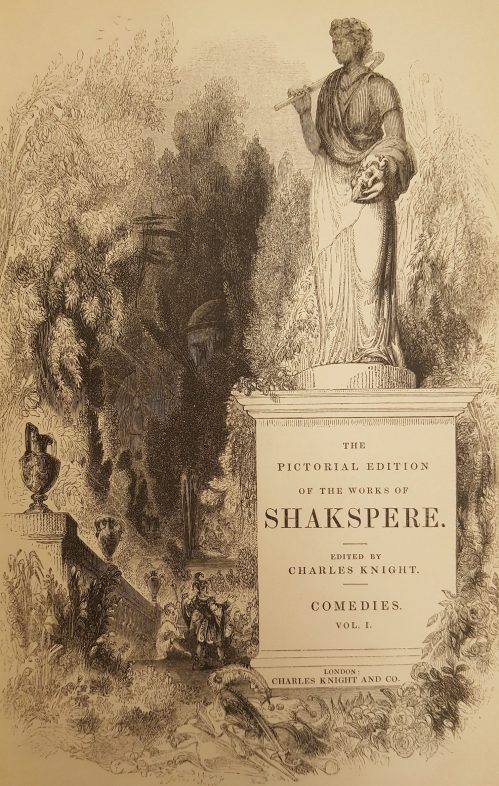

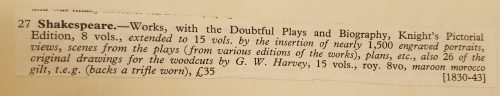

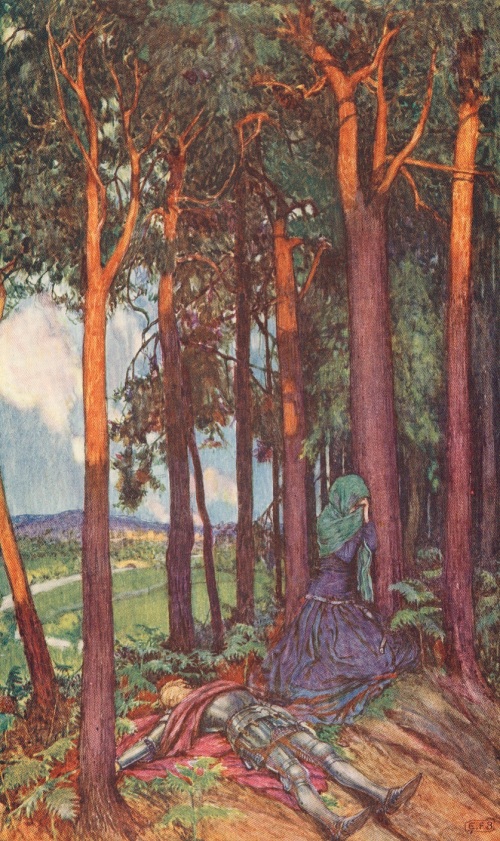

Florence Harrison and Dante Gabriel Rossetti show the dead Lady of Shalott floating into Camelot, with Rossetti’s Lancelot bending down in the cramped few inches of the wood engraving to stare at her ‘lovely face’.

Darlunia Florence Harrison a Dante Gabriel Rossetti’r olygfa pan fo Boneddiges Shalott yn arnofio i Gamelot, gyda Lawnslot yn narlun Rosetti’n

plygu ar ddarn tila o bren i weld ‘ei hwyneb prydferth’.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden wall and gallery,

A pale, pale corpse she floated by,

Deadcold, between the houses high,

Dead into tower’d Camelot.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Guinevere and other poems, illustrated by Florence Harrison. London: Blackie, 1912. Image reproduced with the kind permission of the Florence Susan Harrison Estate.

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

To the planked wharfage came:

Below the stern they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Poems, illustrated by Rossetti etc. London: E. Moxon, 1860.

Elaine

Elaine, the ‘lily maid of Astolat’, became an iconic figure for artists. Tennyson’s poem inscribes Elaine as a specifically Victorian heroine, who wilts away when her love for Lancelot is unrequited.

Daeth Elaine, y ‘forwyn lili o Astolat’, yn ffigwr eiconig ar gyfer arlunwyr. Mae cerdd Tennyson yn cyflwyno Elaine fel arwres Fictoraidd yn benodol, sy’n cilio i’r cysgodion pan ddywed Lawnslot nad yw’n ei charu.

So in her tower alone the maiden sat […]

Death, like a friend’s voice from a distant field

Approaching thro’ the darkness, call’d; the owls

Wailing had power upon her, and she mixt

Her fancies with the sallow-rifted glooms

Of evening, and the moanings of the wind.

![Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson's Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes?].](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/elaine_mss.jpg?w=500&h=600)

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes, London, 1862?]

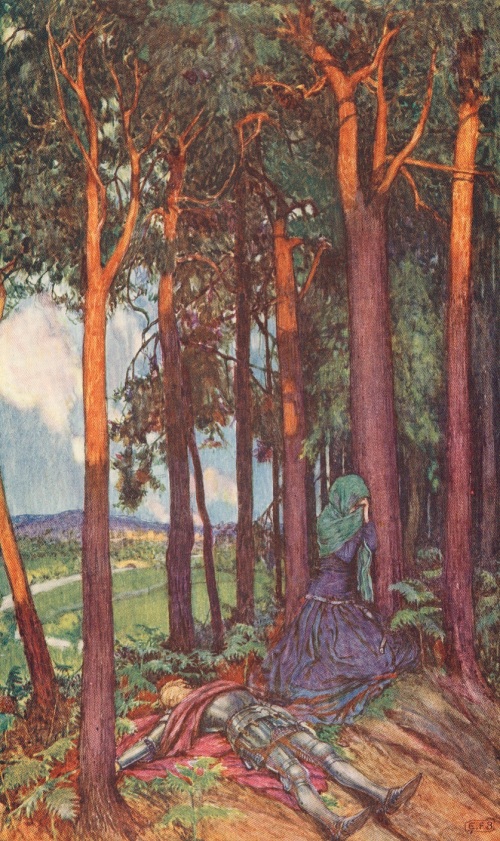

Elaine’s position in a tower, embroidering a ‘

case of silk’ for Lancelot’s shield (which is pictured here by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale), and her final journey down the river towards Camelot, links her thematically and iconographically with Tennyson’s other medieval heroine, the Lady of Shalott.

Mae sefyllfa Elaine yn y tŵr wrth iddi addurno ‘câs o sidan’ ar gyfer tarian Lawnslot (sydd yn y llun hwn gan Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale), ynghyd â’i thaith olaf i lawr yr afon tua Chamelot, yn ei cysylltu’n thematig ac yn eiconig ag arwres ganoloesol arall Tennyson, sef y Feinir o Sialót.

Then fearing rust or soilure fashioned for it

A case of silk, and braided thereupon

All the devices blazoned on the shield

In their own tinct, and added, of her wit,

A border fantasy of branch and flower.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

Illustrators of the period focused on the haunting image of Elaine on her death bed/boat as she carries a lily in her right hand and a love letter to Lancelot in her left (this scene is the frontispiece for Doré’s illustrated edition).

Canolbwyntiodd darlunwyr y cyfnod ar y ddelwedd arswydus o Elaine ar ei gwely angau a hithau’n gafael mewn lili yn ei llaw dde a llythyr cariad i Lawnslot yn ei llaw chwith (y ddelwedd hon sydd ar glawr fersiwn darluniadol Doré).

So those two brethren from the chariot took

And on the black decks laid her in her bed.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

So those two brethren. . .

. . . kissed her quiet brows, and saying to her

“Sister, farewell for ever,” and again

“Farewell, sweet sister,” parted all in tears.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Elaine, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

Oared by the dumb, went upward with the flood–

In her right hand the lily, in her left

The letter… for she did not seem as dead,

But fast asleep, and lay as though she smiled.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Elaine, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

Enid

Unlike the iconic episodes that tend to be favoured in artistic representations of Elaine and the Lady of Shalott, illustrations of Enid are more diverse and represent different narrative moments, from the newly-wed Geraint’s admiration of his wife (seen in the first of Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale’s illustrations here), to her wearing her shabbiest dress and accompanying Geraint on a quest to prove his prowess, convinced as he is of Enid’s infidelity (a moment that is also represented by Brickdale).

Yn wahanol i’r golygfeydd eiconig a gaiff eu dylunio gan amlaf o Elaine a’r Feinir o Sialót, mae darluniau o Enid yn tueddu i fod yn fwy amrywiol wrth iddynt gynrychioli gwahanol naratifau, o edmygedd ei gŵr newydd, Geraint, at ei wraig (y cyntaf o ddarluniau Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale yma) i’r darlun ohoni wedi’i gwisgo’n flêr yng nghwmni Geraint wrth iddo geisio dangos ei gryfder yn wyneb anffyddlondeb ei wraig (a gaiff hefyd ei ddarlunio gan Brickdale).

And as the light of Heaven varies, now

At sunrise, now at sunset, now by night

With moon and trembling stars, so loved Geraint

To make her beauty vary day by day,

In crimsons and in purples and in gems.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911

Brickdale’s images provide a stunning example of Victorian medievalism and suggest her debt to Pre-Raphaelite illustrations. Brickdale seems to delight in the possibilities of this form, her interest in colour carrying through to designs she made after the First World War for stained-glass windows in York Minster.

Mae darluniau Brickdale yn enghraifft arbennig o ganoloesedd Oes Fictoria ac maent yn dangos mor fawr yw ei dyled i ddarluniau Cyn-Raffaëlaidd. Ymddengys i Brickdale fod wrth ei bodd â’r arddull hwn, gyda’i diddordeb mewn lliwiau’n gyson drwy gydol ei chreadigaethau ar ôl y Rhyfel Byd Cyntaf ar gyfer ffenestri gwydr lliw Cadeirlan Efrog.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

Colour book illustrations of this quality were still relatively rare in the period and are a counterpoint to the earlier black and white illustrations of Gustave Doré.

Roedd darluniau lliw o’r fath safon yn dal yn gymharol brin yn y cyfnod hwn, ac maent yn wrthbwynt i ddarluniau du a gwyn blaenorol Gustave Doré.

This heard Geraint, and grasping at his sword,

(It lay beside him in the hollow shield),

Made but a single bound, and with a sweep of it

The russet-bearded head rolled on the floor.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Enid, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867

Guinevere / Gwenfair

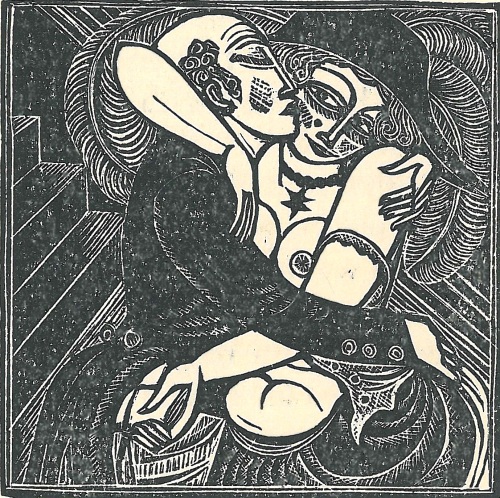

Guinevere, the wife of King Arthur, who commits adultery with Lancelot, is recast in these illustrations as the ‘fallen woman’ familiar from literature and painting of the period. The images revel in the illicit love affair, with Edmund J. Sullivan’s relatively chaste illustration of the ‘boyhood of the year’ giving way to the passion displayed in the images designed by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale and Florence Harrison.

Caiff Gwenfair, gwraig y Brenin Arthur sy’n godinebu â Lawnslot, ei hail-bortreadu yn y darluniau fel ‘y ddynes odinebus’ sy’n gyfarwydd mewn llenyddiaeth a darluniau o’r cyfnod. Mae’r darluniau’n gorfoleddu ym mhechod y gyfathrach, ac mae darluniau cymharol bur Edmund J. Sullivan o ‘fachgendod y flwyddyn’ yn llai amlwg na chreadigaethau Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale a Florence Harrison.

Then, in the boyhood of the year,

Sir Launcelot and Queen Guinevere

Rode thro’ the coverts of the deer,

With blissful treble ringing clear.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, A dream of fair women & other poems, illustrated by Edmund J. Sullivan. London: Grant Richards, 1900.

The similar poses in these two images suggest that Harrison might have been influenced by Brickdale’s image, although the motif of the embracing couple is common in mid-nineteenth-century book illustration.

Mae’r tebygrwydd yn y ddau ddarlun yn awgrymu i Harrison gael ei dylanwadu gan ddarlun Brickdale, er i’r motiff o gofleidio rhwng cariadon fod yn gyffredin mewn darluniau llyfrau yn y bedwaredd ganrif ar bymtheg.

It was their last hour,

A madness of farewells.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Guinevere and other poems, illustrated by Florence Harrison. London: Blackie, 1912. Image reproduced with the kind permission of the Florence Susan Harrison Estate.

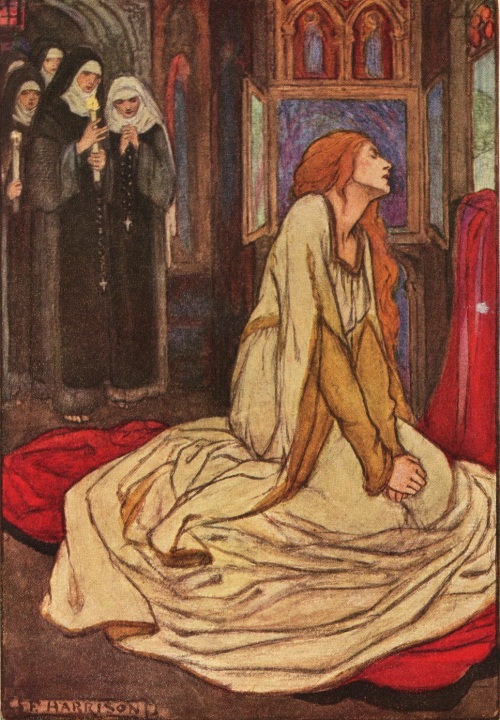

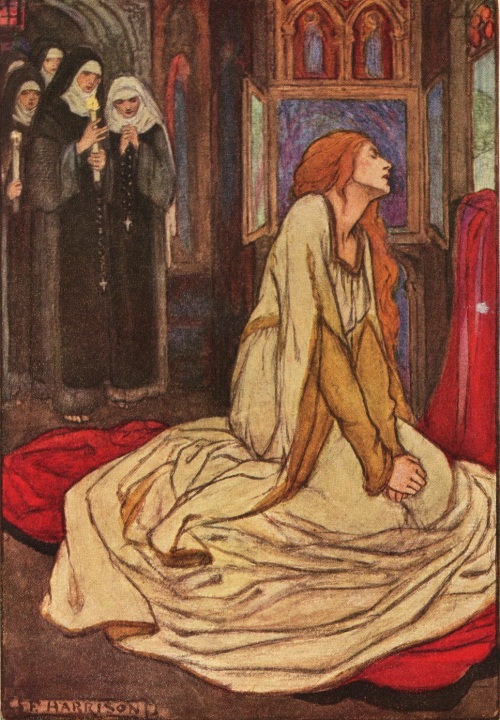

The illustrations of the penitent Guinevere are equally striking, with Harrison’s heroine wringing her hands in despair.

Mae darluniau o edifeirwch Gwenfair yr un mor drawiadol, gydag arwres Harrison yn griddfan â’i dwylo mewn anobaith.

We needs must love the highest when we see it.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Guinevere and other poems, illustrated by Florence Harrison. London: Blackie, 1923. Image reproduced with the kind permission of the Florence Susan Harrison Estate.

Gustave Doré’s Guinevere is literally fallen, lying prostrate at Arthur’s feet like the adulterous wife in Augustus Leopold Egg’s painting ‘Past and Present’ (1858; Tate Gallery, London).

Mae Gwenfair wedi syrthio’n llythrennol fel y ddynes odinebus yn narlun Gustave Doré, ac mae’n gorwedd yn swrth wrth draed Arthur fel y gwna’r wraig odinebus yn narlun Augustus Leopold Egg, Past and Present (1858; Galeri Tate, Llundain).

He paus’s, and in the pause she crept an inch

Nearer, and laid her hands about his feet.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Guinevere, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

Vivien

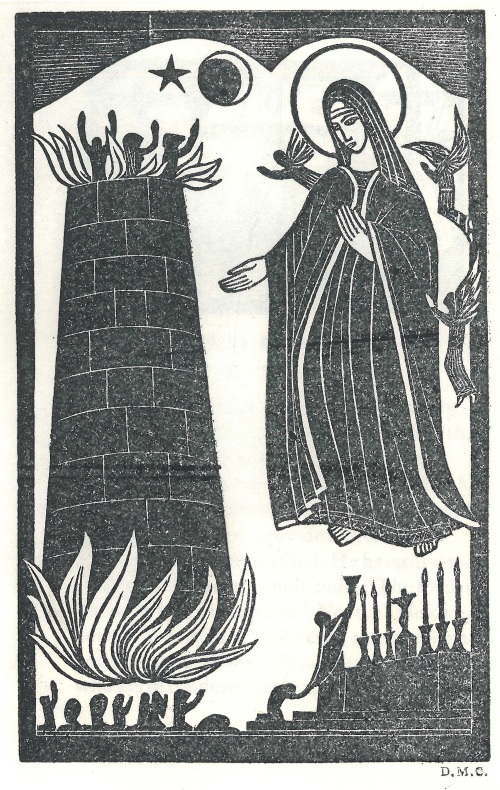

The ‘wily Vivien’, who seduces Merlin into telling her a charm that enables her to imprison him in an oak tree, provides rich opportunities for book illustrators.

Mae’r ‘Vivien gyfrwys’, sy’n hudo Myrddin i roi gwybod iddi am swyn y mae hi’n ei ddefnyddio i’w garcharu mewn derwen, yn cynnig cyfleoedd euraidd i ddarlunwyr llyfrau.

‘It is not worth the keeping: let it go:

But shall it? answer, darling, answer, no.

And trust me not at all or all in all.

O Master, do ye love my tender rhyme?’

![Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson's Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes?]](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/vivian_mss.jpg?w=500&h=686)

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes, London, 1862?]

Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale’s seductress plays with Merlin’s beard as he places his hand upon his brow, aware of the doom that is about to befall him.

Mae Vivien fel y’i darlunir gan Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale yn anwesu barf Myrddin wrth iddo gyffwrdd ei ael, yn llwyr ymwybodol o’r anffawd sydd ar fin ei daro.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

Brickdale depicts another, less obvious, scene in her illustration of a Queen who has been ‘charmed’ by her husband so that no other man can see her (apart from a male viewer of this illustration, of course). It is this magic charm that is passed on to Merlin and, by him, to Vivien.

Mae Brickdale yn darlunio golygfa arall, llai amlwg, yn ei darlun o Frenhines sydd wedi’i ‘swyno‘ gan ei gŵr fel na all unrhyw ddyn arall ei gweld (heblaw dyn sy’n edrych ar y darlun, wrth reswm). Y swyn hon a gaiff ei phasio i Fyrddin, a chanddo ef i Vivien.

And so by force they dragged him to the King.

And then he taught the King to charm the Queen

In such-wise, that no man could see her more,

Nor saw she save the King, who wrought the charm.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Idylls of the King, illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

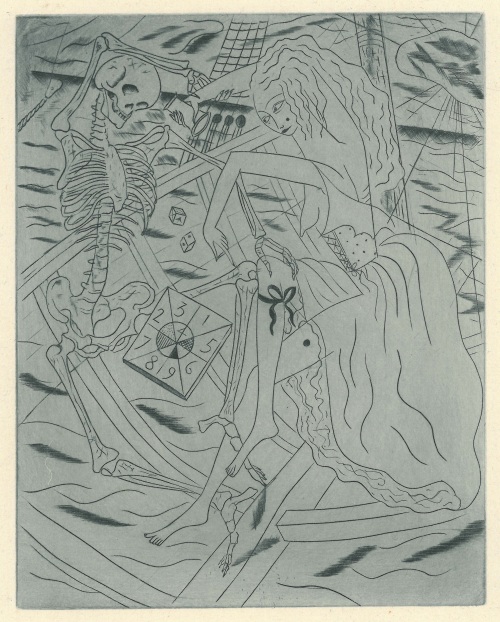

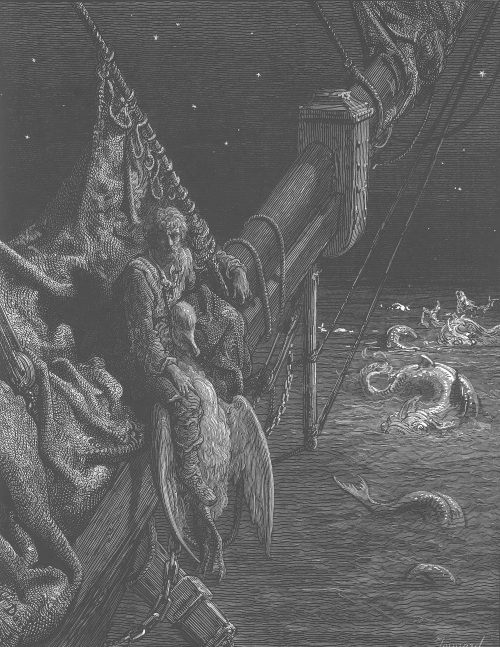

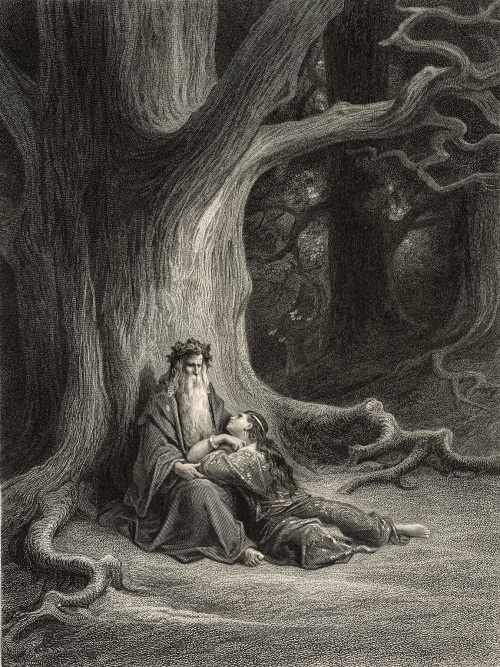

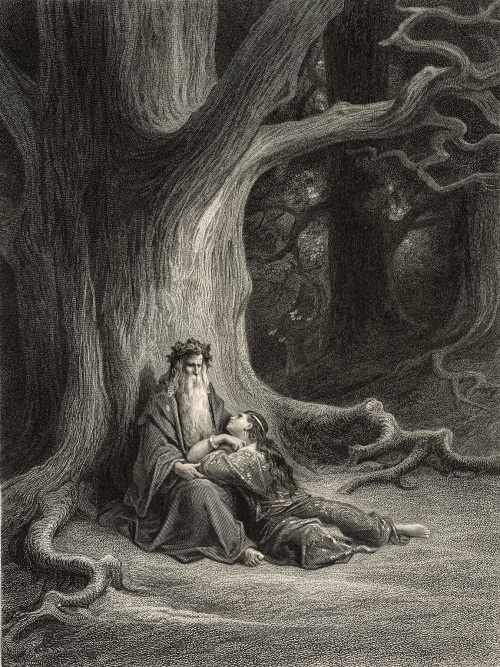

Gustave Doré’s atmospheric black and white plates point to the climax of the story as Vivien follows Merlin into the wild wood and seduces him under an oak tree, the snake-like roots of which creep around the couple.

Mae’r platiau du a gwyn, llawn awyrgylch gan Gustave Doré yn cyfeirio at uchafbwynt yr hanes wrth i Vivien ddilyn Myrddin i’r goedwig wyllt a’i hudo o dan dderwen, â’i wreiddiau megis nadroedd yn llercian o amgylch y ddau.

And then she followed Merlin all the way,

Even to the wild woods of Broceliande.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Vivien, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

Before an oak, so hollow, huge and old

It looked a tower of ivied masonwork,

At Merlin’s feet the wily Vivien lay.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Vivien, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

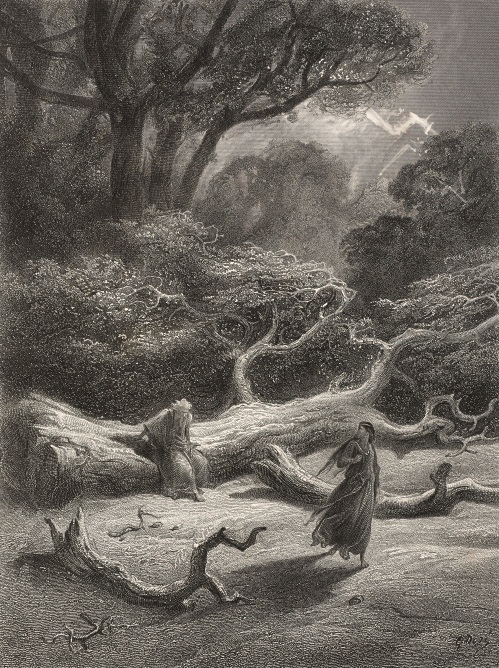

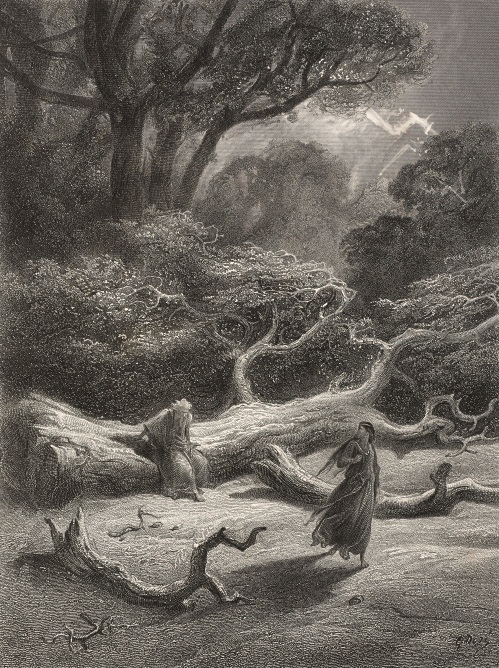

The final scene here shows the broken oak tree, which has been struck by lightning, and the equally broken Merlin, who has ‘told her all the

charm’.

Mae’r olygfa olaf hon yn dangos y dderwen wedi torri, wedi’i tharo gan fellten, a Myrddin yntau wedi torri wedi iddo ‘ddweud y swyn wrthi’.

For Merlin, overtalked and overworn,

Had yielded, told her all the charm, and slept.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Vivien, illustrated by Gustave Doré. London: Edward Moxon, 1867.

Mariana

There are two Marianas represented here: the first is from a poem published by Tennyson in 1830, which takes as its source the figure of Mariana from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, who waits for her lover to return. The second, ‘Mariana in the South’, published in 1832, tells of a female living in a state of extreme loneliness. The illustrations suggest the extent to which Mariana is inevitably bound up in the cultural moment in which she is pictured.

John Everett Millais’ heroine buries her face in her hands in a pose that Millais used in other illustrations.

Caiff dwy Fariana eu darlunio: y gyntaf wedi’i seilio ar ddelwedd mewn cerdd a gyfansoddodd Tennyson ym 1830, sy’n delweddu Mariana fel y’i disgrifir yn nrama Shakespeare, Measure for Measure, yn disgwyl i’w chariad ddychwelyd. Yr ail yw ‘Mariana yn y De’, a gyhoeddwyd ym 1832, sy’n adrodd hanes menyw’n byw mewn unigedd dirfawr. Mae’r darluniau’n cyfleu’r modd y mae Mariana’n anorfod yn gaeth i’r diwylliant y gwelwn hi ynddo.

Mae arwres John Everett Millais yn claddu ei hwyneb yn ei dwylo mewn modd y defnyddiodd Millais yn ei ddarluniau eraill.

“My life is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, ‘Mariana’, in Poems, illustrated by J. E. Millais. London: E. Moxon, 1857.

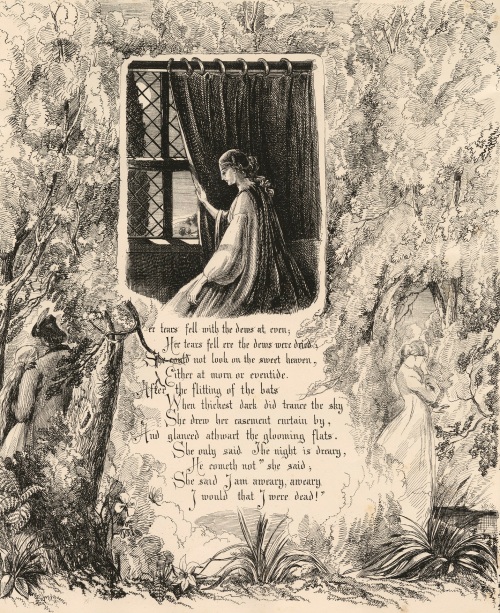

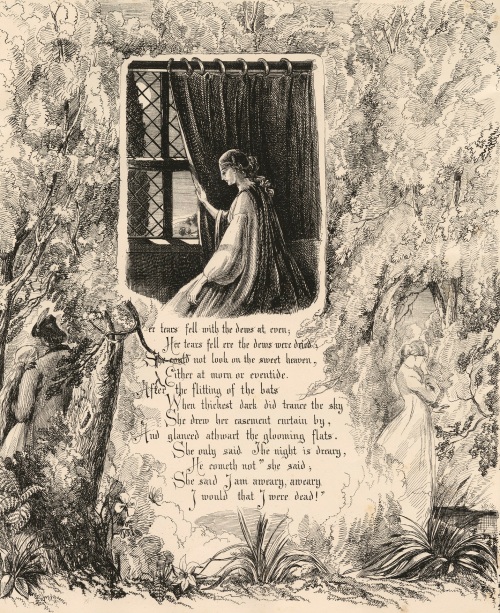

Lamb’s Mariana looks like a quintessential Victorian heroine as she meekly holds back a curtain and peers out of the window.

Mae Mariana fel y’i darlunir gan Lamb yn edrych fel arwres Fictoraidd bwysig wrth iddi dynnu’r llen ac edrych drwy’r ffenestr.

With blackest moss the flower-plots

Were thickly crusted, one and all:

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the pear to the gable-wall.

The broken sheds look’d sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Mariana, with etchings by Mary Montgomerie Lamb (Violet Fane). Worthing: O. Breads, 1863.

Sullivan’s Mariana, however, is an altogether more powerful and frustrated figure, who languishes in her fashionable fin de siècle dress.

Mariana fel y’i darlunir gan Sullivan, fodd bynnag, yn ymddangos fel dynes sy’n fwy pwerus ond rhwystredig ar y cyfan wrth iddi ymfalchïo’n ei ffrog fin de siècle.

“My life is dreary,

He cometh not,” she said;

She said, “I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, A dream of fair women & other poems, illustrated by Edmund J. Sullivan. London: Grant Richards, 1900.

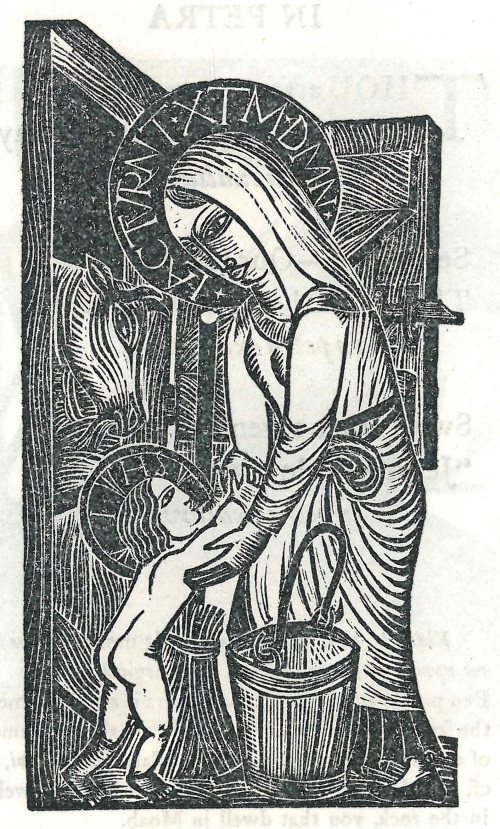

The explicitly religious overtones of ‘Mariana in the South’ in which Mariana prays to the Virgin Mary, is represented in the fervor of Rossetti’s heroine, who passionately kisses Christ’s feet, and Sullivan’s Mariana, who prays so ardently that we can see the throbbing veins in her hand.

Mae’r dylanwadau crefyddol amlwg ar ‘Mariana yn y De’, â Mariana’n gweddïo i’r Forwyn Fair, i’w gweld yn drawiadol yn arwres Rossetti, wrth iddi gusanu traed Crist, ac yn yr un modd Mariana fel y’i darlunir gan Sullivan, wrth iddi weddïo mor galed hyd nes y gwelwn y gwythiennau yn curo yn ei dwylo.

And on the liquid mirror glow’d

The clear perfection of her face.

‘Is this the form,’ she made her moan,

‘That won his praises night and morn?’

And ‘Ah,’ she said, ‘but I wake alone,

I sleep forgotten, I wake forlorn.’

Alfred Lord Tennyson, ‘Mariana in the South’ in Poems, illustrated by D. G. Rossetti. London : E. Moxon, 1859.

Till all the crimson changed, and past

Into deep orange o’er the sea,

Low on her knees herself she cast,

Before Our Lady murmur’d she:

Complaining, ‘Mother, give me grace

To help me of my weary load.’

Alfred Lord Tennyson, ‘Mariana in the South’, in A dream of fair women & other poems, illustrated by Edmund J. Sullivan. London: Grant Richards, 1900.

The exhibition is open to all, and will run until December 2016.

Mae’r arddangosfa yn agored i bawb, a bydd yn para tan fis Rhagfyr 2016.

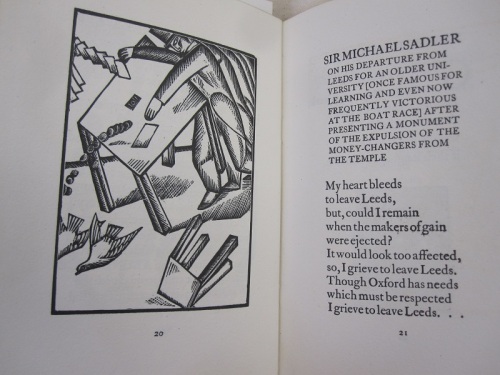

According to ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’, prior to the outbreak of war all four of the Barbier brothers had well-established careers; Paul E A. Barbier had been Professor of French at the University of Leeds since 1903, Edmond was the assistant examiner in oral and written French to the Central Welsh Board, Georges was the manager of coal firm ‘Messrs Instone’ and Jules, a civil engineer in North America. Because of their French Nationality, the brothers had completed military service with the French Army well before the war (Paul completed his in 1889), making them no strangers to a military environment. According to the booklet, in August 1914 all four men, along with their brother-in-law Raoul Vaillant de Guélis (married to their sister Marie) were called up by the French state and sent to France.

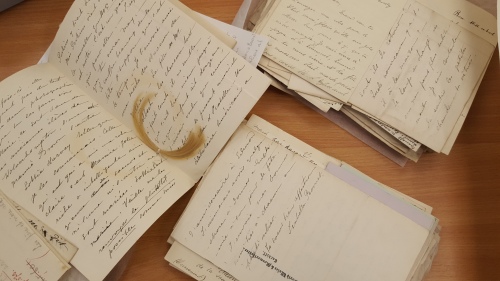

According to ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’, prior to the outbreak of war all four of the Barbier brothers had well-established careers; Paul E A. Barbier had been Professor of French at the University of Leeds since 1903, Edmond was the assistant examiner in oral and written French to the Central Welsh Board, Georges was the manager of coal firm ‘Messrs Instone’ and Jules, a civil engineer in North America. Because of their French Nationality, the brothers had completed military service with the French Army well before the war (Paul completed his in 1889), making them no strangers to a military environment. According to the booklet, in August 1914 all four men, along with their brother-in-law Raoul Vaillant de Guélis (married to their sister Marie) were called up by the French state and sent to France. Jules and Georges remained ‘poilus’ (ordinary field soldiers for the French army). Much of the archive from the war years is dedicated to correspondence from Paul E. A. Barbier (or Paul Barbier Fils, as in son, as he is known) to his wife Cécile. From what I have grasped after reading his letters, it seems Paul Barbier Fils had a reasonably ‘comfortable’ wartime experience; that is to say, he regularly talks of eating well and playing bridge with his brother Edmond. In numerous letters, he says he is in ‘good health and spirits’ and regularly returns to the UK on leave, which he documents. According to the letters in the archive, Paul Barbier Fils also remained in close contact with his colleagues at the University of Leeds. For example, there are letters from the Vice Chancellor of the university who asks for Paul’s opinion on various university matters. There is even a letter to Paul dated 29th June 1915 from the Vice Chancellor who says he has been in contact with the French Embassy in London attempting to release Paul from the army, unfortunately without success.

Jules and Georges remained ‘poilus’ (ordinary field soldiers for the French army). Much of the archive from the war years is dedicated to correspondence from Paul E. A. Barbier (or Paul Barbier Fils, as in son, as he is known) to his wife Cécile. From what I have grasped after reading his letters, it seems Paul Barbier Fils had a reasonably ‘comfortable’ wartime experience; that is to say, he regularly talks of eating well and playing bridge with his brother Edmond. In numerous letters, he says he is in ‘good health and spirits’ and regularly returns to the UK on leave, which he documents. According to the letters in the archive, Paul Barbier Fils also remained in close contact with his colleagues at the University of Leeds. For example, there are letters from the Vice Chancellor of the university who asks for Paul’s opinion on various university matters. There is even a letter to Paul dated 29th June 1915 from the Vice Chancellor who says he has been in contact with the French Embassy in London attempting to release Paul from the army, unfortunately without success. Georges Barbier, on the other hand, seemed to have had the most difficult war experience out of the family members who went to the Front. In 1916 he returned to London from the front due to illness to work for the Coal Board. In letters to his brothers and mother, he talks of suffering from night-blindness and having very little food, if any. His wife Nan died a few years later, leaving him a widower with two children. Fortunately, the three other brothers who remained in France survived, and in 1919 were demobilised from the army, returning to their peacetime lives in Cardiff. Their brother-in-law, Raoul Vaillant de Guélis was not so fortunate and died of pneumonia in 1916. His wife Marie never remarried and raised her two children along with those of her brother George after his death in 1921. One of her children, Jacques Vaillant de Guélis became a Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, an undercover spy who carried out missions in France during the Second World War. I do not know much about his life yet, but I am excited to discover more over the upcoming weeks.

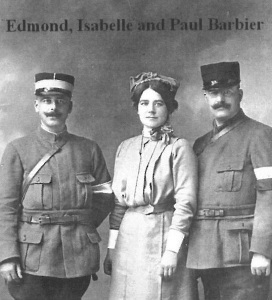

Georges Barbier, on the other hand, seemed to have had the most difficult war experience out of the family members who went to the Front. In 1916 he returned to London from the front due to illness to work for the Coal Board. In letters to his brothers and mother, he talks of suffering from night-blindness and having very little food, if any. His wife Nan died a few years later, leaving him a widower with two children. Fortunately, the three other brothers who remained in France survived, and in 1919 were demobilised from the army, returning to their peacetime lives in Cardiff. Their brother-in-law, Raoul Vaillant de Guélis was not so fortunate and died of pneumonia in 1916. His wife Marie never remarried and raised her two children along with those of her brother George after his death in 1921. One of her children, Jacques Vaillant de Guélis became a Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, an undercover spy who carried out missions in France during the Second World War. I do not know much about his life yet, but I am excited to discover more over the upcoming weeks. Finally, while the brothers were at the Front, their younger sister, Isabelle Barbier, spent time in France as a nurse during WW1. Unlike her brothers, there is little correspondence from Isabelle during the war years throughout the archive, but ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’ gives detailed accounts about her time as an assistant to Dame Maud McCarthy, Matron in Chief to the British Expeditionary Forces. On page 7 of the booklet, there is a lovely picture of Isabelle with her brothers Edmond and Paul, as well as a picture of her in uniform wearing the Royal Red Cross – presumably she was awarded this, but I am unsure when. It is something I would like to find more about when I speak to the previous owner of the archive. All in all, the archive offers insights into the wartime experiences of this remarkable family and it has been particularly fascinating to discover how Paul Barbier Fils continued his interests and worked remotely with the University of Leeds. I hope the former owner is able to answer some of the questions which I have raised, as I feel there are some interesting pointers for future research.

Finally, while the brothers were at the Front, their younger sister, Isabelle Barbier, spent time in France as a nurse during WW1. Unlike her brothers, there is little correspondence from Isabelle during the war years throughout the archive, but ‘Barbier Voices from the Great War Part 1’ gives detailed accounts about her time as an assistant to Dame Maud McCarthy, Matron in Chief to the British Expeditionary Forces. On page 7 of the booklet, there is a lovely picture of Isabelle with her brothers Edmond and Paul, as well as a picture of her in uniform wearing the Royal Red Cross – presumably she was awarded this, but I am unsure when. It is something I would like to find more about when I speak to the previous owner of the archive. All in all, the archive offers insights into the wartime experiences of this remarkable family and it has been particularly fascinating to discover how Paul Barbier Fils continued his interests and worked remotely with the University of Leeds. I hope the former owner is able to answer some of the questions which I have raised, as I feel there are some interesting pointers for future research.

![Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson's Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes?].](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/elaine_mss.jpg?w=500&h=600)

![Alfred Lord Tennyson, Selections from Tennyson's Idylls of the King, [illuminated by Sir Richard R. Holmes?]](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/vivian_mss.jpg?w=500&h=686)

![David Jones, frontispiece. Llyfr y pregeth-wr. [Ecclesiastes].](https://scolarcardiff.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/opening1.jpg?w=500)